An Interview on Investing with Speedwell Research's Drew Cohen

Reproducing Drew's uneditied interview feature on Compounding Quality

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo that is available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

A shortened version of this interview orginally appeared on Compounding Quality’s Newsletter. We wanted to provide the full unedited interview though, which is what is below.

All questions are from Pieter Slegers of Compounding Quality.

We hope you enjoy it!

1) Can you say a bit more about yourself? Who is Drew? And how did Speedwell Research come to life?

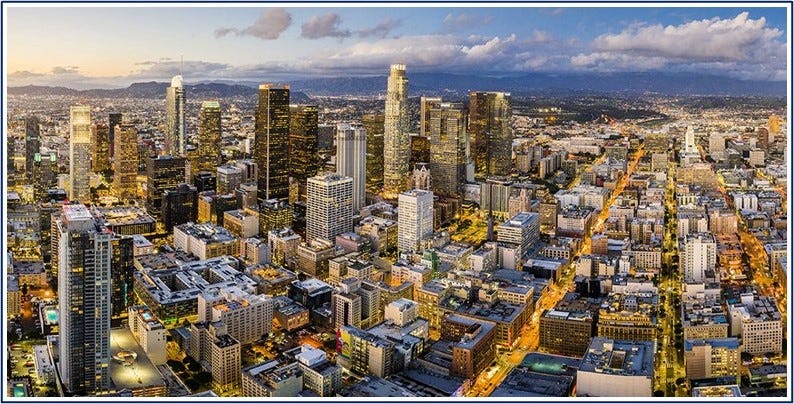

I’ve been interested in investing since I was young and bought my first stock at 14. You can say the next few years I learned all the ways to not invest—I was a short-term trader and macro focused, and never did any real research. Eventually, as the cliché goes, I found Buffett and Munger and changed my ways. After graduating USC with two degrees in Accounting and Business Administration, I worked at Goldman Sachs in New York in their Investment Research Division covering financial companies. This gave me firsthand knowledge in what was lacking from investment bank-produced research.

After Goldman, I moved to San Francisco to work at Capital Group, which is one of the largest mutual fund managers in the world with over $2 trillion in assets. I was lucky that I got to focus on internet companies, as well as getting some broad generalist exposure and the opportunity to work on some late-stage private deals.

Capital Group was a fantastic place to learn a lot about how hundreds of billions of dollars are allocated and their large size meant that I got to meet all sorts of CEOs, billionaires, and entrepreneurs.

However, I wanted to work for myself and have full control of my own investment process without having to worry about non-investment prerogatives or company politics.

Speedwell Research was created to give investors the research that I wanted to write at Goldman Sachs and that I wish existed when I was at Capital Group. I never understood why most investment reports have hundreds of graphs when only a few are meaningful. Nor why most “reports” are done in power point, when it is easier to understand full sentences than bullet points. I think there is a lot of wisdom in the fact the Jeff Bezos made his executive write full memos at Amazon and Steve Jobs banned power points from Apple.

There is an added benefit of writing so much: the in-depth research we produce also helps my own investment process —it’s hard to fool yourself if you have to write an 80-page report explaining your reasoning.

2) Every investor is unique. How would you describe yourself? Would you describe yourself as a quality investor? A quality investor with a value tilt? A value investor…?

The terminology investors use to describe themselves tends to change overtime. For a long time value investor meant that you did company-specific research and only bought the stock if you thought it traded for less than intrinsic value. Buffett always called himself a value investor, even after he had more Charlie Munger and Phil Fisher influence (which now is usually considered quality or growth investing). However, nowadays, value investor tends to mean you only buy stocks that trade at low book values or earnings multiples and are usually of lower quality businesses.

The way I invest is I want to know all of the assumptions that are baked into the investment. Then I want to see the returns associated with those assumptions. I do this with a Reverse DCF, which allows me to see the various returns under a lot of different scenarios. I tend to like the investments most where the downside risk is minimal (i.e. the most draconian “likely” assumptions don’t have you losing money) and relatively conservative assumptions have you earning around what the market has done historically. It is very specific to the company though, and if there is strong optionality from new business lines, I might be willing to accept a lower return from their existing core business.

While this may sound quantitative, it really isn’t. The majority of the process is qualitative. I spend a long time studying the history of the business. While the past can’t necessarily predict the future, it can at least tell you how the business did under a variety of different circumstances. I go back to the beginning and read every single earnings transcript from the company and try to get a strong sense of how the business has acted overtime. This is because I believe learning about a business is much like learning about an organism: they tend to have predictable behaviors overtime.

Additionally, deep research is critical to building conviction. You have to have enough confidence in all of the research you’ve done that you can be sanguine when the stock moves. If you have a tendency of becoming fearful when your stock is down, you likely didn’t do enough research.

Lastly, I highly value predictability in my investments. This will cut out a lot of businesses that require high growth rates far into the future in order to rationalize a return. This also means that I tend toward higher “quality” businesses. (Quality in quotes because everyone tends to have a different definition). It also means that I will avoid turnarounds and businesses that are still figuring out their business models.

3) Buffett summarizes his investment philosophy as follows:

1. Find wonderful businesses;

2. With competent management;

3. Which trade at fair valuation levels

How would you define your investment philosophy?

It feels like it’s a set-up to disagree with anything Buffett says. Essentially, I do the same thing, but the differences would fall between what assumptions we are comfortable making and how you define “wonderful”.

I tend to think how hard it would be to compete against company XYZ. I like businesses that have what I call interlocking moats. That means that in order to even get beyond one competitive advantage, you also need to have another. Marketplace network effects are a classic example of this because in order to get large supply, you need a large user base and you can’t get the second without the first.

There are many other examples though, like RH. If you want to build large and beautiful Design Galleries like them, you need to have multiple collections of furniture to fill up the space. To build up the collections, you need a brand that top designers want to work with. If you want to draw people into the Galleries to become top of mind, you need a higher frequency service like restaurants. Since you are going directly to consumers, instead of relying on trade designers to get you customers, you will need inhouse interior designers to avoid being intermediated by a 3rd party designer later in the purchase journey. If you want the best deals on real estate, you need a record of building aesthetically beautiful stores and can prove you draw traffic to the area.

In order to truly copy RH’s model, there is at least 5 things right there that you have to do right: real estate development, attracting design talent, running an interior design service, supporting a wide selection of furniture, and creating compelling hospitality experiences. If you don’t do everything, then you are not a direct competitor—that is because other furniture makers compete on the product, but RH is competing on the whole experience and getting to the customer earlier in the purchase journey.

Put simply, my investment philosophy might be defined as focusing on 1) competitively advantaged businesses that are 2) well-run with 3) high predictability and 4) some positive upside optionality that offer a 5) satisfactory returns under conservative assumptions.

4) You dive deep in companies (80-page investment cases). How long does it take you to create such a case? And does it make you more comfortable when making investment decisions?

It can vary but generally 5-8 weeks.

This may sound a little odd, but I don’t believe good decisions are “made”. If I think of many of the big decisions I made in my life, I was never really making a decision: it was always obvious to me that I should accept the Goldman Sachs or Capital Group offer, and I spent surprisingly little time contemplating whether I should quit my job to work for myself. Hopefully this isn’t a sign of my lack of introspection, but rather exemplifies that if you know something, you know it—and if you are thinking from the position of a “decision that needs to be made” it is already an admittance that you do not know the answer. There are times in life where you may be forced to make a decision, but I don’t believe that is the case with investing, at least not my way of investing.

We only ruminate on questions that we do not know the answer to.

If you do enough research, you don’t need to make decisions because answers become clearer and clearer. Maybe you need to sit and read 60 earnings transcripts to build conviction on stock, even if you cannot point exactly to what you learned that changed your mind, but your path of action became clearer, nevertheless. The research is melding your opinion in a subtle way that shouldn’t require a leap at the end. And it may also be that no amount of research can compel you to action—that is okay too.

This is not to say you will never make mistakes, but you will never need to sit and think about what is the “right” decision is. The idea that you can sit in a chair staring at a wall and think your way to a good decision is not just fallacious, it is harmful.

5) You wrote Deep Dives on Constellation Software, Copart, Axon, Costar Group, … with which company do you feel the most comfortable today?

I’ll interpret comfort as meaning comfort in the business model and not the valuation. Copart is an incredible business because they don’t just have one strong moat, but each moat is independently strong, but also interlocking (as explained with RH earlier). For those that don’t know their business, they basically help tell an insurance company when a car needs to be totaled after an accident (which means it is not worth repairing it and should be sold for scrap) and arrange for it to be picked up and sold through auction.

To try to compete against them you need to have land close to cities, but you can’t get the land because the land is much more expensive today—and even if you could buy it, it is near impossible to get the permits to turn it into a junkyard. This alone is a formidable barrier to entry, but even if a deep-pocketed competitor overpaid for land, they would still struggle to get business.

This is because they would have no totaled vehicles to sell. This is for two reasons: 1) the network effects (no one will give you vehicle supply until you have a lot of buyers to bid on the vehicles), but also the fact that Copart has a whole logistics operation to pick up cars, and a vast repository of data to tell the insurer when to total a car. Copart is directly integrated into the insurers system to the point that the insurance company outsourced critical functions like titling to Copart. Lastly, and critically, Copart has a history of very strong service levels, including during catastrophe events where vehicle volumes can surge 10x.

All of this means that you need to get multiple elements in place (land, global marketplace, insurance company integrations, service levels, CAT protocols, data-based tools) just to begin to compete against Copart.

6) What’s the best investment decision you’ve ever made?

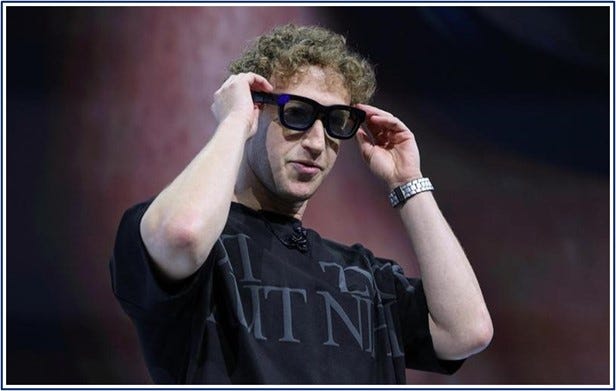

We published our Meta Research Report in January 2023. Our Reverse DCF showed that the market was pricing in 0-3% growth forever and Reality Labs being a net negative value. Here is how we thought about that market assumption at the time. Below is a chart from our Meta Research report. It shows that there are 4 variables to revenues.

First, despite the noise, the number of users were not falling and were actually growing. Second, time spent was growing as well with Reels usage increasing. Third is ad load, which is well in Meta’s control as they can always put an ad against any sort of content they host. So that left just the fourth factor, ad price, in question.

Meta’s ad prices are set by auction. They were being hit because of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) and to a lesser extent because of a Covid-driven ecommerce spending boom reversion. ATT decreased the data Meta received from their mobile app and thus hurt their ability to target ads and to measure when an ad was successful. To solve for this issue, they were spending >$30bn in AI infrastructure to build models that could rebuild the signal with less data input. Additionally, they were pushing advertisers to install their “conversion API” on the server back-end, so data would not have to be passed through iOS.

An investor at this point in time only had to believe these efforts would at least mean Meta could grow revenues 0-3% to get a historical market average return of ~10% (as our Reverse DCF showed). Furthermore, this also assumed that the ~$20bn a year in Reality Labs they are spending would become worthless.

I considered these assumptions to be very conservative, if not outright draconian. At the time we published our report, the stock was trading around $120 a share. I added all the way down to the bottom and made it my largest position by cost basis.

7) What’s the worst investment decision you’ve ever made?

It wasn’t bad in terms of outcome, but my analysis was wrong on Etsy. I believe I was right in judging the fact that they have a strong competitive position, but the problem was they are strong in an area (handmade) that people don’t care much about.

This made me think more about how a company can be the best in the world at something, but if people don’t care, it doesn’t matter. They are ultimately optimizing for the wrong thing. Furthermore, they cannot change their organization to pivot to things the consumer cares more about (like faster shipping or cheap prices in this case) without sacrificing a key value prop of their business.

In Etsy’s case, being handmade means its products cannot sit in a fulfillment warehouse and cannot be mass-produced, and thus will always cost more. These are structural elements that are inextricably linked to offering handmade items. There simply is no way Etsy can match Amazon’s shipping speeds or Temu’s prices without changing what they are known for. Which is another way of saying they have a competitive advantage in an area few people care about.

8) What’s a famous investment rule you disagree with?

I think the idea of staying in your circle of competence is either misunderstood or wrong. As it is usually explained, there are things that you are not well versed in and so should avoid entertaining investments in that area, sticking to things you know well. Implicit in this idea is a lack of ability to learn and understand new fields. I dislike this idea on a personal level because I love learning. But I don’t believe this is what Buffett meant anyway.

I think keeping within your circle of competence isn’t about not learning new industries or investing in areas you have never invested in prior, but rather is about humility in the limits of prediction.

Porsche AG may be a company I am able to understand, but it may be outside of my circle of competence to know whether they will continue to sell >300k cars a year far into the future. Conversely, I have confidence Floor & Decor will continue to be a leader in selling LVP (luxury vinyl plank) flooring. This is despite the fact that I had no idea what LVP was 5 years ago and had to learn, but I knew what a Porsche was since I was a kid. The circle of competence isn’t about familiarity or simplicity in the business model, but about confidence in your assumptions. Though of course if you don’t understand the industry or business well you couldn’t possibly have confidence in any assumptions.

9) Which key characteristics should a good investor have?

Self-awareness. We all have so many biases that we can’t realistically hope to never fall prey to. But if you are self-aware you can at least notice when you are likely falling prey to them and short-circuit that behavior. Too often someone decides an investment is good for reasons that have nothing to do with the investment and are solely because they want a good investment.

People can make an investment their identity, which means they are no longer rationally analyzing a situation, but rather filtering their decisions through a prism of desire. They may like an investment because of the positive association in brings or because they think it will solve a problem in their life (whether that is financial or something more egoistic like respect doesn’t matter). They will cling to an investment that is clearly a losing investment because selling isn’t just losing money, but losing an identity. They are acting out of need—and Mr. Market doesn’t care about your unfilled desires.

One of the more impressive feats of Warren Buffett is that he has no problem with people publicly heralding one of his investment—and can himself publicly praise a company—to only then unceremoniously part with it when he believes the facts or opportunities have changed (as we just saw with Apple).

It is a flawed hope to think you can just be unemotional by employing logic because logic does not direct emotions. However, with self-awareness you can recognize emotions as distinct from logic, which in practice can be just as good as it allows you to not act on them.

10) What would you do differently if you could start all over again today?

Just do what I am doing but earlier. I waited a long time to publicly publish my research for fear it wasn’t good enough. I never felt comfortable putting my name on anything publicly until I was convinced my research was better than what most professionals produced. It was unnecessary to wait that long though.

If started Speedwell Research in college I am sure the research would have been much lower quality and perhaps I would have gotten a more negative reception initially, but I would have learned quickly. It’s important to remember that no one really cares about your worst work.

Naval Ravikant talks about how once you stop “trading” today for tomorrow you are retired. That doesn’t mean you don’t work, but that the work you are doing you never want to stop doing. By that definition, the goal should be to retire as soon as possible, and ultimately, I am very fortunate I could consider myself retired at such a young age either way.

11) Warren and Charlie are known as vivid readers. How much do you read?

“I know not one intelligent person that does not constantly read”.

I got a jump of anxiety reading that Charlie Munger quote when I just graduated high school. I decided that I need to read way more of everything. I read over 30 books that summer.

There was a several year period where I averaged a book a week, but now I read a lot more annual reports and earnings transcripts that bleed into my reading time. I’m probably closer to 1 book every 2-3 weeks now (I don’t shy away from very long books though).

I also have stopped reading books to completion if I don’t feel I am getting anything out of them. If I’m not compelled to finish a book after I am half way through it, I stop. This means I complete fewer books, but I feel I am utilizing my limited reading time better. “Books read this year” is somewhat a vanity metric, but I also acknowledge that focusing on that goal can help you read more than you would have otherwise.

12) What’s the best piece of advice for someone who will keep investing for the next 20, 30 and 40 years?

While I am a long-term investor, there are very few companies you would have wanted to hold for the past 40 years. I take that to mean you can’t be complacent and must continue to research and analyze the businesses you already own. The flip side though is that if you do find a great company, you shouldn’t be so valuation sensitive that you miss the 40-year return because you thought the 4 year return was good.

13) If there are rumors that a respected investor sold shares in a business you own, do you still believe in the company?*

*Question rephrased to eliminate naming a specific investor.

When I say this, it shouldn’t be misinterpreted for a lack of respect for other intelligent investors. However, I don’t care at all what other people do. This may sound arrogant, but please suspend judgement for a moment.

The reason why we spend hundreds of hours analyzing a business is to thoroughly understand it. The purpose of the research is to build confidence in our assumptions. The valuation then dictates what the return those assumptions will yield. We are open to contradictory opinions, but we don’t blindly follow anyone—we only follow our research and our judgement. It doesn’t make sense to go through this whole process to just “borrow” someone else’s judgement.

I have no idea why another investor may make a different decision. The fear of course is that they discovered a critical fact we missed. However, given our research process, that is unlikely, but not impossible. More likely is simply that an investor changed their mind on the risks they are willing to accept in an investment. All investments have risks, and sometimes an investor may change their mind on whether they deem the risks inherent in an investment to be worth the return.

Now if an investor explained their rationale for why they exited a position, of course I would listen to that argument and they might be able to convince me to change my mind. But what’s the point of doing research if you aren’t going to form and hold your own opinion?

Certainly, a great investor selling (like Warren Buffett did with RH in 2023) is a reason to consider if you missed something, but if you come to the same conclusion you did prior then think nothing more of it.

Of course, there are a slew of different reasons someone may have sold that are not related to the investment in question. An investor could have found a different opportunity they liked more, a LP could have redeemed forcing the sale of a position, or the fund could have changed their mandate under investor pressure to avoid investing in certain business. If you are so concerned with what other investors are doing, you should really just give them your money and let them invest for you.

14) Any book recommendations to share with our audience?

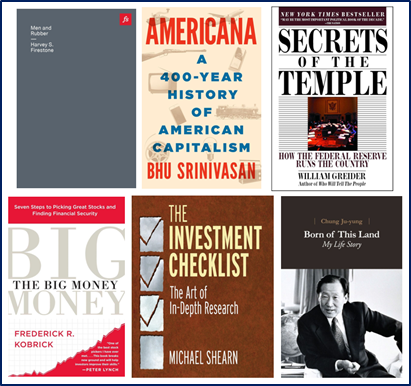

It looks like you’ve already mentioned many of the best investing books, but I’ll share a few that are less talked about:

The Big Money by mutual fund manager Frederick Kobrick has some interesting insights, particularly around the interplay between research and conviction.

The Investment Checklist by Michael Shearn is a solid and straightforward book on things to look for in an investment.

Secrets of The Temple by William Greider is a great history of the Federal Reserve and focuses a lot on the high inflationary period of the 70s.

Americana by Bhu Srinivasan is an interesting history of American Capitalism by telling the story of a single industry that defined each era.

Men and Rubber by Harvey Firestone is a great business book by an entrepreneur who was contemporary with Henery Ford and Thomas Edison.

Born of This Land by Chung Ju-yung is the story of Hyundai, which became a business conglomerate that spanned many different industries (construction, shipbuilding, passenger cars, semiconductors, financials, chemicals, department stores). It also is really interesting because they were instrumental to building up South Korea’s domestic economy.

Thank you for reading this interview! If you want to learn more about Speedwell Research’s Philosophy click here!

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Members Plus also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).

*At the time of this writing, one or more contributors to this piece may have a position in securities discussed. Furthermore, accounts one or more contributors advise on may also have positions in securities discussed. This may change without notice. Nothing here constitutes investment advice. Please see our full disclaimers here.