Copart Business History

Speedwell Research: Business History

This is an excerpt from our Copart research report, which goes over Copart’s early history. It is just the beginning (~15 pages) of our ~22k word deep dive (80+ pages). We hope you enjoy it! Get the full Copart report, among others, by becoming a Speedwell member today!

For an in-depth discussion of Copart, see our episode on The Synopsis (Spotify, Apple Podcasts)!

Please email us at info@speedwellresearch.com for any questions, concerns, or comments. See our full disclaimer on our website.

Founding History.

Born in Oklahoma in the 1940s, Willis Johnson spent most of his youth ping-ponging around the country as his dad worked odd jobs and sifted out unique opportunities. His dad wasn’t against manual labor, but he spent most of his energy searching for business opportunities in the local paper. One such opportunity landed the Johnson family ownership of an Arkansas dairy farm. Willis learned the value of discipline and the importance of hard work first-hand as he attended to their cows and the farm whenever he wasn’t in school. He recalls waking up at 3:30am to milk the cows, driving into town to hit the creamery by 6:30am before attending school, then returning to the creamery to pick up the empty cans after school and milking the cows again in the evening. However, it wasn’t too long before his dad auctioned off the farm and they wound (back) up in California.

Willis’ mom would read the classified ads to his father who was illiterate but analyzed each business opportunity. One of his more notable business endeavors was when he bought the assets of a bankrupt construction company and tasked the young Willis and one of his friends with dismantling their equipment and inventory into portable pieces of metal. The plan was to simply sell it for scrap iron and move on, but Willis’ dad realized he could regularly buy cars for $5 and scrap them for $17, so they stayed in the dismantling business. Soon enough, they had to get a farm to store all the junk and get the requisite permit after the city hassled them: they then officially owned a junkyard.

Willis would learn a great deal not just about how to dismantle cars, but also things like what each part could be worth and what to look for in a wrecked car. This learning was eventually put on pause though, as he enlisted to serve in the Vietnam War. As a forward observer in the army, it was his job to stand out in front of the unit and check for ambushes and booby traps. He saw horrendous action: half of his unit was killed. All of the survivors received Purple Hearts, which are awarded for sustaining injury in the line of duty. Willis would pull mortar shrapnel out of his body for years afterwards. After leaving Vietnam a year later, he threw his Purple Heart in a drawer and didn’t think about it again for decades.

After returning home, Willis resumed work at his dad’s junkyard until quarrels with his increasingly drunk father led him to strike out on his own. He started working at Safeway, a supermarket, before eventually finding a junkyard whose owners were set to retire. He convinced them to take a fraction of the $75k asking price as a down payment with interest-only payments in the interim. To save money, Willis and his wife moved into a trailer on the property. It was named Mathew Auto Dismantlers, after the nearby air force base.

Initially, Willis focused on scrap metal. He would find cars that were so beaten up that they had no longer had any value as a car, and then melt them down to sell the raw materials. However, many of the cars he bought still had some working parts, which could be resold to DIYers or mechanic shops at a premium to melt value. In order to build out the parts side of the business, he focused on getting higher quality cars (keep in mind “quality” here is relative to literal junk). Willis had a few novel insights though: instead of selling parts in their entirety, like an engine, he would break them down into their constituent parts. Whereas a competitor would sell an engine for $400, he sold the distributor, alternator, carburetor, etc., individually, and could get $700 for the same engine, only dismantled. Additionally, selling parts individually meant he wouldn’t have to guarantee the whole motor worked, especially if it broke soon after a sale. Willis would also clean the parts and paint them when necessary to make them look new. He would then display them in a retail format store with shelves instead of strewn around a yard like competitors did, which further garnered an additional premium for the parts.

The next thing Willis did exhibited his innate business savviness. In order to differentiate himself, he specialized in specific car parts. However, instead of picking the most popular models, he picked items that specifically weren’t “hot-selling” products. He chose to specialize in Chrysler, Dodge, and Plymouth parts. Dismantlers thought he was foolish, but were nevertheless happy to sell him their slow-moving parts, and also refer customers in search of those.

By specializing, he could serve a customer need that competitors not only weren’t, but had no desire to address. Focusing on items his suppliers didn’t want to carry allowed him to get good pricing, while simultaneously generating customer referrals from these suppliers. Customers were more willing to drive far out to get their Chrysler or Dodge products since he was the only supplier in the region. Essentially, by focusing on “slow-moving”, unique parts, he could actually make them turn faster. By specializing, he was able to increase the geographical reach of his yard and make the assortment of goods turnover quicker while simultaneously insulating himself from local competition since he had a differentiated offering. These changes worked in a big way: his sales jumped to $3,500 a day to $3,500 a month.

As his business grew, he needed more inventory. He started visiting Bob’s Tow Service, also known as BTS Auctions, who would tow totaled cars on behalf of an insurance company and then auction them off to local dismantlers, car rebuilders, and mechanic shops. (A totaled car is a vehicle that incurred damage and the insurance company deemed it would be cheaper for them to sell the damaged vehicle and pay the policyholder a settlement instead of trying to repair the vehicle. A totaled car may also be called salvaged). Willis would spend $10k a week on salvaged cars to haul back to his yard.

With his yard swelling with car parts, he spent $110k on a computer, which he later noted cost more than two houses at the time. However, it was more than worth the investment, as it allowed him to keep track of all of his inventory at a time competitors were using a flurry of paper and file drawers. It taught him which parts of a car to scrap and which he should stock more of across thousands of different parts that varied by make, model, and year. (He would later also build a computerized system for the California DMV. Since the manual title transfer processing was forcing him to store cars on his lot for weeks longer than ideal, which ballooned his working capital, he developed an electronic solution, at his own expense, for the DMV that cut weeks out of the process).

Showing his entrepreneurial nature, Willis opened up several related junkyard auto businesses around then, including: 1) a minitruck-focused junkyard, 2) Today Radiator, which focused on used radiators, 3) a used auto-parts-focused store, 4) a foreign-car-focused junkyard, and 5) U-Pull-It, which operated yards full of damaged cars that customers pulled parts off themselves, making it the cheapest way to buy parts.

He even started a dismantling magazine so he could advertise to more repair shops, insurance companies, and mechanics. Thinking back to his farming days when farmers would store grain together in a co-op, he thought the magazine was a similar concept since there was a “co-op” of parts dealers using the magazine. He decided to call it Copart.

After some time, Willis became BTS Auctions’ largest buyer, and while it was an important source of vehicles for him, the owner wanted to retire and his kids wanted to sell the business. They wanted $1mn for the business, even though it had just $100k in equipment and brought in $65k pre-tax. However, Willis knew BTS Auctions had basically been on autopilot for years, and that there was enormous growth potential. He had also thought that when a business is family owned, salaries and other family expenses were included in the financials, which he would not have to incur. As such, he partnered with Peter Kay, a friend of his, each putting up $50k as a downpayment, to purchase the company. Since Willis had to use his other businesses as collateral, he got a controlling 51% stake. In 1982, he became the proud owner of his first car auction.

The recession in the mid-70s crippled advertising revenues from his Copart magazine, and since it was already legally incorporated, he decided that rather than pay to set up a new legal structure for BTS, he would use the magazine’s existing one. Copart Auctions was born.

Business History.

While Willis was focused on all of his different automotive businesses, Peter was in charge of Copart’s day-to-day operations. In short order, they opened a second Copart yard in Sacramento. They realized that the shorter the distance each car had to be towed to get to a yard, the cheaper it would be to service that unit, so they kept looking to add locations. Their third yard was opened in Richmond, San Francisco.

Peter, however, was quickly approaching 70, and spending more and more time with his racehorses over Copart, and it started to show. When a few lapsed bills were overlooked, Willis had enough. Willis gave Peter an ultimatum: They would each write a number on a piece of paper, and Peter could buy the business at Willis’ number or sell at his own. Peter sold.

With Willis now fully in charge, he started making changes. Sealed bids were changed to live auctions. Guests were allowed to come in so long as they could get a licensed dismantler (a requirement to bid on salvage pool cars) to take liability over them. And he kept adding yards as opportunities presented themselves.

The biggest business transformation was a change in the incentives and economics of the auction business. Just as cleaning the car parts he sold increased the price he could command, doing the same for his salvaged cars yielded a similar result. He wanted to make the cars look nicer, but knew the insurance companies would be reluctant to spend money on this. So instead, he thought, what if there was a way to split the increase in price from making the cars look nicer?

At the time, it might cost about $200 to pick up, store, and auction off a car. Willis wanted to instead incur that cost, plus the cost of cleaning up the car, in exchange for a percentage of the proceeds once the car sold: 20% for old and highly damaged cars and 10% for everything else. The result was that both the insurance companies and Copart generated higher proceeds.

This arrangement, which Willis called the Percentage Incentive Program, or PIP, also solved another issue insurance companies had. A burned-out car may have fetched only $25 in an auction, but cost that same $200 for Copart to pick up and process. The insurance companies were losing money on each of those units. Under PIP, Copart instead would be the one to lose out on that car by incurring expenses less than their portion of proceeds. The kicker is that Copart would only offer PIP if an insurance company contracted out all of their cars in a region to Copart. So Copart would lose on a fire-damaged vehicle, but make it back on a lightly damaged, newer car. Economics aside, Willis liked how he was now aligned with his customers: they both wanted the highest price for the cars, whereas before his revenues only increased with volume.

In 1989, he met Jay Adair, a recent high school graduate, and his daughter’s boyfriend. Jay showed a curiosity in the salvage business, partially driven by his amazement that anyone could make money from junkyards. He would pepper Willis with questions about the business, and before long, Willis was taking Jay with him to investigate new properties for purchase. After Jay’s first year of college, he decided it wasn’t a good use of his time and that he wanted to become a businessman. When he told Willis, Willis handed him a broom.

Jay started running more of Copart, starting with the titling department that interfaced with the DMV, and then moving to the customer service department. He excelled at work both in the office and out in the yard, but he was worried that Copart could never grow to the size that it would be big enough for him to take on meaningful responsibility and make a lot of money. That all changed in 1991, when IAA, an auto auction competitor, went public. Flipping through the prospectus, Willis thought that if IAA could do it, then so could they. He traditionally eschewed debt, but liked the idea of raising capital that he wouldn’t have to pay back. He recalls thinking that “going public would allow Copart to not just grow—but grow big”.

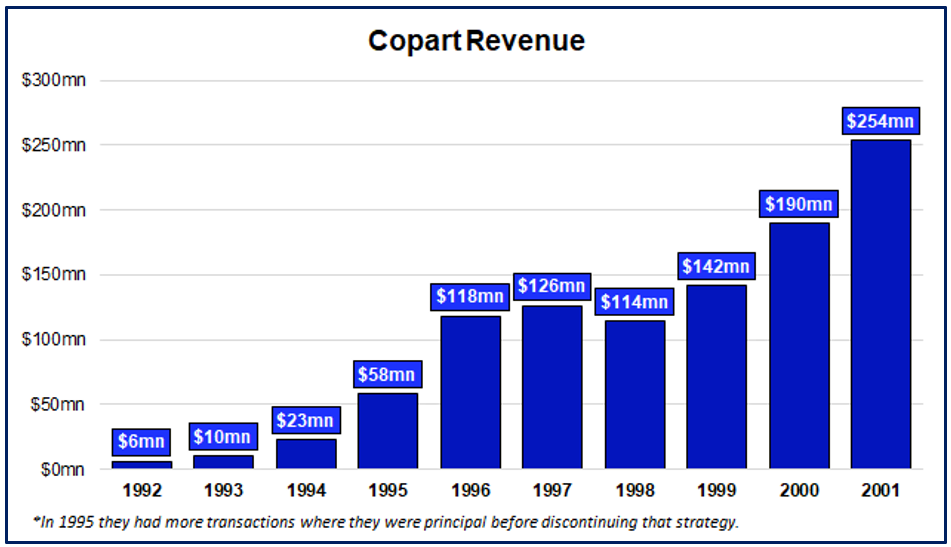

Before going public though, they had to get larger. So he got in touch with a Wall Street investment banker to help raise $10mn in a private round. He was able to raise that amount as a convertible that paid 8% interest and would convert into a 26% stake of the company. Willis and Jay then embarked on a growth phase, tripling their footprint to about a dozen yards and generating $1.4mn in EBIT on $10mn in sales.

That was enough that their banker thought they could complete a public offering. They sold 2mn shares at $12 a share, raising over $20mn after underwriting fees. Whereas just a few years earlier the whole operation was only a few local locations, they were now a New York Stock Exchange listed company valued at over $80mn. Willis’ 40% stake made him wealthier than he could have ever dreamt, but he was just getting started.

The proceeds were their ammo, and Copart was prepared to go to war with IAA. They would try to swallow up as many mom & pop junkyards, as well as several regional chains, as quickly as they could, as they knew IAA was breathing down their neck.

Whereas Willis often made handshake deals to come back and sign contracts on the hood of a salvaged car in cowboy boots, IAA showed up in limos with lawyers in suits. The IAA approach turned off some junkyard owners but impressed many others. They battled for acquisitions as the industry rapidly consolidated. By 1996, Copart had 49 locations. Revenues grew to a sizeable $118mn and $18mn of EBIT. This growth, though, was funded by a near doubling of shares outstanding, as they used their stock as currency to acquire more properties. This included a secondary offering at $19.25 in 1995 that raised an additional ~$30mn.

With many junkyard locations hard to replicate because of permitting requirements, land scarcity, and the public generally against allowing a new junk yard to open up anywhere near them, the race was on to acquire properties in as many markets as they could. However, whereas IAA was privy to buying big and expensive lots in large cities like Chicago for $7-9mn, Copart would opt for smaller suburban yards in Longview or Lufkin for $1.5-2mn. Copart was focused on building a network more than buying any one namesake location. They thought more locations would allow them to tow cars a lower distance, which would make their operation more efficient, even if it came at the cost of losing some city-center business for the time being.

Interestingly, despite IAA being bigger, Willis was often winning bids against them because IAA bought companies “the Wall Street way”, based on accounting earnings. Willis, on the other hand, knew that a lot of these family-run businesses would use the company as a sort of piggy bank to buy personal cars or pay salaries to family members who didn’t work much (something he learned when he originally bought BTS Auctions). As such, Willis would size up how many cars they sold at auction and what he thought Copart would make if they owned it. IAA thought more in terms of how an acquisition would look from a pro forma GAAP perspective.

A big difference between Copart and IAA was what they did after acquiring a property. IAA would more or less leave it alone, thinking it was more urgent to acquire the next property than integrate the one they had just purchased. In contrast, Copart would train staff members in the Copart way and change operations so each yard would run the same. At one point, they even slowed growth to focus on unifying all of their properties into a single ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) system. It took two years and $3mn, but by 1997, they started rolling out their new computer system yard by yard. This made it much easier to manage the increasingly national operation, and keep track of and identify any particular yards that had abnormal inefficiencies.

Copart’s readiness to adopt technology and experiment has always set them apart from their competition. In the late 90s, Jay started hearing about “.coms”. At first, he thought they could list their cars online to limit the paper they were wasting—it took over 8,000 sheets of paper to circulate the weekly auction list of cars.

But then he realized that they could use the internet to help solve one of their largest pain points: buyers were hiring people to bid on their behalf at the car auctions, paying them $150 every time they won a car. He thought it was silly that people could make $2-3k a day just standing around and raising a paddle. This was a prime use case for the internet to serve—buyers could come the day before and view the cars, then place a bid online for $35 instead of paying a contractor to stand in the live auction. Jay was right. Copart’s online platform generated $1mn in sales the first quarter it launched.

There was one particular transaction that stood out, and in retrospect, anticipated a multi-decade shift in how cars would be purchased. The auction winner of a car sold in San Diego was a buyer in Connecticut. Whereas cars were always sold locally, maybe occasionally regionally, this was an instance of someone buying a car across the country, sight-unseen. Jay called up the buyer, and he said that while he knew what he was buying, it would be helpful if Copart added pictures online. Jay proceeded to buy 55 cameras and teach each of Copart’s General Managers how to take pictures of a car. With photo listings set up two quarters later, that $1mn of online sales per quarter grew to $10mn, and they closed 2000 with a total of $190mn in revenues.

Still though, bids were not being placed live during the actual auction, only prior. The first iteration of online bidding was born in 2001 and dubbed Virtual Bidding 1 (VB1). It required building out large structures to house the auctions inside with large TVs that showed pictures of the current car. No longer were auctions held out in the open in the yards. The internet system was linked to a row of employees at computers who would monitor online bids and signal to the auctioneer if there was an internet bid. This allowed the internet bidder to be enmeshed in the live auction happening on the floor.

With online auctions, the thing they noticed was not just that buyers from far away markets were participating in the auctions, but that the auction prices were increasing. This meant higher returns for the insurance company and a higher cut for Copart, since over half of their cars were on the PIP model. (“Returns” is industry terminology for the sales proceeds as a % of average cash value or pre-accident value. If a car is worth $10k before an accident and Copart sells it for $3k, then that is a return of 30%).

When 9/11 hit, financial markets were spooked and there was a fear that people would be reluctant to travel again for a long time. Planes were flying at just 5% capacity. Willis and Jay were on a flight to visit a yard with just a handful of passengers, but when they got off to rent a car, they noticed it was slammed. Willis realized that miles driven would go up as people avoided flying, but he lacked the cash needed to continue their yard acquisition spree. They had over 70 locations by then, but in order to continue growing, he went back to Wall Street for another secondary offering, this time raising $116mn at $29 a share.

VB1 was creating operational issues though, and further growth almost assured it would only get worse. The employees that monitored the online bids couldn’t watch the screens for more than an hour at a time without error rates skyrocketing. Their largest yards still had yet to incorporate the system for fears it would be too hectic and bids would get lost. Buyers stopped coming to the yards in-person to bid online, which interfered with the live competition component. Taking the middle option of quasi-online and in-person was an optimization of mediocrity. Jay told Willis they would either have to go all in on the internet or abandon the effort…

This concludes the free excerpt of our report. In the full report, we continue the Business History with the development and definition of Copart’s “job”, the evolution of their bidding system, Hurricane Katrina, and more. We then delve into their domination of North America and international expansion as well as detail their competitive moats and future growth opportunities.

See below for the full table of contents, and subscribe to get access to the full >80 page Copart research report in PDF! Members can also access our Constellation Software, Floor and Decor, Meta, Copart, Walker Dunlop, and Etsy reports, as well as the DJY Research archives.

Table of Contents

Founding History.

Business History.

Business.

Industry and Auction Dynamics.

IAA.

Copart Model.

Copart vs IAA.

Beyond North America.

Beyond Salvage.

Beyond Cars.

ROIC and Capital Allocation.

Revenue Build.

Risks.

Summary Model.

Historical Financials.

Financial Model.

Conclusion.

Or if you’re not quite ready to read the full report, drop your email below for free updates. And or more free Copart content, see our episode on The Synopsis (Spotify, Apple Podcasts).

In this podcast on Copart, Speedwell Research covers everything from Founder Willis Johnson’s early business career to the industry dynamics, and how Copart became the global, salvage marketplace auction leader. Investors can learn a lot from Willis Johnson’s early business intuition and movement from the lowest wrung of the salvage vehicle value chain as a liquidator to ultimately a critical service provider for insurance companies. We draw on Speedwell’s 85 page report, released in May 2023, to teach not just about Copart’s business, strategy, and formidable competitive advantages, but also to parse out cultural factors that distinguish truly great companies.