If the Model Doesn't Work, Don't Fix It: A Look at Traditional Apparel Retailers, Zara, and Shein

Retail Industry Issues, Estimating Demand, and Two Better Models

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

Intro.

Imagine a business where you buy something you are not sure you’ll be able to sell.

Where you pay upfront for product that you don’t receive until many months later.

Where it is a given that taste will change every year or so, making your product obsolete.

Where the literal weather can impact its salability.

Where success can mean a double-digit operating margin.

And failure means: loss-making discounting, brand image degradation, supply chain havoc, and not atypically, bankruptcy.

This is the traditional apparel industry.

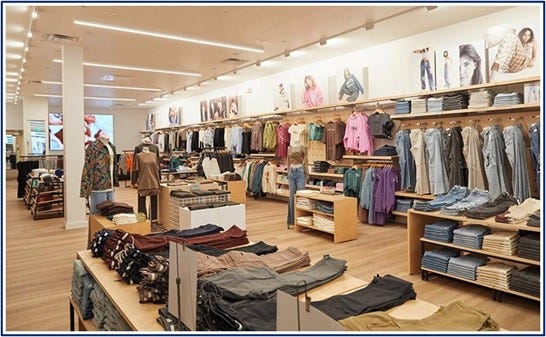

Traditional Clothing Apparel.

The key issue with retail generally is estimating demand. Since traditional retailers need to get physical goods in physical stores, getting the right goods in the right amounts is critical. This is hard enough as it is, but the challenge is compounded by the fact that there is a long lag between orders being placed and items arriving in store. Within this time, popular styles can change, making an entire order potentially outdated before it even arrives. Or, conversely, a style can prove to be very popular, but the store lacks sufficient inventory, so they lose sales.

The problem with estimating demand is a lack of information on what consumers want. Retailers may hire industry experts, fashion designers, and run competitive research, but the truth is there is only one real source of accurate information: a sale.

Each sale creates information. Information is needed to pick the right inventory. The right inventory is needed to make a sale.

For the traditional clothing retailer, there is no easy answer as the information they need to make an informed decision doesn’t arrive until it is too late to make a different decision. Order too little inventory and you lose an opportunity to make a sale. Order too much inventory and you can be stuck with an unsellable product.

The problem gets worse though. If you have extra inventory, then you could be forced to discount. If you discount, you might wreck your brand image, lose sales of undiscounted merchandise, or compel consumers in the future to defer purchases until they see a discount. If you have too little inventory, then you not only lose sales, but you may be sitting with a half empty store, which also hurts your brand image. To restock the store, you may be forced to pay premiums to expedite orders.

Traditional retailers have centralized planning and purchasing departments who will place bulk orders 3-6 months ahead of time. It is already hard to keep the right amount of inventory in the right places when the product is something fairly predictable like tires or energy drinks, where past information provides insight into future sales patterns, but no such reliable signal can be drawn from prior clothing seasons.

So, if there is no way to predict accurately, then perhaps a retailer could avoid predicting all together.

This is the insight of Amancio Ortega, founder of Zara.

The Zara Model.

Where other fashion retailers tried to create or predict fashion trends, Zara decided to simply follow them. This model would never work though with a lead time of 3-6 months—which was typical for most traditional retailers. Instead, he would create a new category of apparel called “Fast Fashion”, with much quicker turn around times.

First, Amancio Ortega would focus on cutting down lead times. Owning their own apparel factory was crucial to this, as it ensured the capacity existed and allowed them to communicate new designs quickly. Since the factory was near the design center, no time was wasted shipping samples back and forth, as is typical when outsourcing to Asia.

The design process didn’t include a team coming up with far out ideas, but rather scouring the world for already existing designs that were proving popular. However, since they still couldn’t be sure if these designs would be successful, they would size down their orders. Instead of manufacturing enough clothing for a season, they would create enough to stock their store for weeks. This meant that if a design “missed” there was less lost on inventory. Conversely, if it was a hit, they could quickly create more similar items, perhaps changing the color or patterns a bit.

It turned out that the low order quantities had another impact: it drove more spontaneous sales as consumers worried they would never see the same item again—which was generally true. It also meant that they could experiment with more SKUs to see what worked or didn’t. Zara would produce over 10,000 distinct products annually, whereas competitors were doing 60% to 80% less. The more designs also meant that if a shopper revisited a Zara store 2 weeks later, most of the items would be different.

In-sourcing production, closely integrating designers with the manufacturer, “drawing inspiration” from popular designs, keeping order quantity relatively small, and short lead times all worked to create a system that minimized discounted or unwanted inventory while maximizing sales volume.

Whereas a traditional retailer had to plan for 3-6 months out, Zara would look just 2-4 weeks out. The shorter time frame, coupled with smaller order sizes, meant that losses from poorly received items were more limited and successes from hits could be sized up quickly. This effectively allowed Zara to invest more in inventory as they received more information.

This model works especially well because Zara is generally considered lower price, at least compared to the expensive designer styles they mimic. Most Zara shoppers do not expect their purchases to be lifetime buys, but rather it is the trendiness that is the initial attraction. The consumer may no longer like the style before the clothing falls apart (but not always!). Their clothing does get the criticism for being cheaply made, but that doesn’t matter because their consumers value style, a lot of options that are quickly refreshed, and relatively low prices.

The net result of this is inventory turns of 4x versus peers at 2-3x and mid-teens operating margins. It is key to note that the traditional retailer cannot easily copy Zara since they cannot turn ideas into product as quickly without in-housing manufacturing and forfeiting any sense of a “unique style” in order to churn out enough SKUs of popular designs. There are simply styles that The Gap or Abercrombie & Fitch will never want to make for fear it will tarnish their image. Zara has no such trepidations, which allows them to experiment broadly.

The same way a traditional retailer can’t accommodate the Zara model though, Zara can’t accommodate the next iteration in this model: Shein.

The Shein Model.

In many ways, Shein took the Zara model to the next level. Whereas Zara would make tens of thousands of an design, Shein would make just 100 to 200 at once. Zara closely integrated the designer and manufacturer; in the Shein model the manufacturer essentially is the designer deciding what to make. Zara launches 3-5x more new SKUs annually than a traditional retailer; Shein launches 75-150x.

What makes the Shein model different is how it relies even less on demand predictions. Each SKU may have as few as 100 items behind it, which can be scaled up quickly should the demand be there for more. Instead of centralizing a design department or copying other popular designs, they essentially just try everything. With thousands of manufacturers who have leeway to make any design they want, they do still get copycat items, but also a ton of novel garments.

As an online retailer they do not have to worry about where to place inventory and they can quickly reorder successful designs. The lack of footprint also reduces their overhead costs and since most consumers are willing to wait 1-2 weeks for their order, shipping costs aren’t prohibitively expensive. Eliminating mark-up from a wholesaler, costs of physical stores, and losses from potential unsold inventory all help support very low prices, which in turn drives a consumer who is willing to spend more, often compulsively.

A side effect of having so many items that are so cheap is there is a lot of value in discovery and recommendation. Whereas a traditional retailer--and even Zara to an extent--play curator of what is hot or not, Shein just throws the whims of thousands of manufacturers at consumers, who together create an estimated >300k new items annually. To help solve for the need of a discovery function, Shein leaned into influencer marketing and offered 10-20% commissions to influencers for completed sales. This helped drive “Shein hauls” on TikTok where influencers would review items they liked, effectively serving as a recommendation system and customer acquisition tool simultaneously.

Putting all of this together, you get a retailer that produces products almost as TikTok serves content. There is little presumption that Shein knows what you want, but rather they utilize “user feedback” (i.e. purchases) to decide what to produce more of. Manufacturers can in turn use this data to offer more similar products or kill product lines. The direct manufacturer connection doesn’t just make coordination quicker, but lowers prices by cutting out a layer of markups. The online only presence allows them to carry an incredible amount of SKUs that would be impossible to replicate in a store. The lack of store presence helps simplify inventory management and further saves costs. The influencer marketing campaign wouldn’t be possible unless there was value in someone sifting through all sorts of different SKUs. All of these pieces work together to get a sale with minimal information on what they should produce in the first place. The system guides itself to the right answer without any need for a crystal ball.

While Shein is still private, estimates have put their inventory turns at 8-12x, or over twice as high as Zara’s. Revenue estimates put Shein neck-in-neck with Zara, if not having already slightly surpassed them.

Can’t Move, Won’t Move.

While all of these models could survive, including the traditional apparel retailer, the point we are dancing around is that in order to address a business problem, each element of the business must be optimized for that singular purpose. Deeply ingrained in both Zara’s and Shein’s models in how to deal with estimating demand when you don’t have enough information to accurately do it.

The Zara model takes one approach, piggy backing off of popular designs and limiting batches. Shein instead abdicates any inkling of a belief that they know what the consumer wants with micro-orders that can automatically size up as demand comes in.

Nevertheless, despite issues with the traditional apparel model, most retailers haven’t adapted to a different system that would allow them to circumvent many of these drawbacks. This is for a simple reason: in order to do so, they’d have to start all over and rebuild their business system with a different aim in mind.

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Plus members also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).