Meta Platforms Business History

Speedwell Research: Business History

Below is an excerpt from our 160+ page Meta Platforms report. This post contains the first part of our “Meta Business History” section. We hope you enjoy it! Please email us at info@speedwellresearch.com for any questions, concerns, or comments. See our full disclaimer on our website.

For an in-depth discussion of Meta, see our podcast episode on The Synopsis: Apple, Spotify

Founding History.

Born in a New York suburb to a dentist and a psychiatrist, Mark Zuckerberg was drawn to two things: programming and empire building games. At just 10 years old, he threw a fit demanding to be taken to a Barnes & Noble to get a C++ coding textbook. However, Mark was disappointed in the superficiality of the book “for dummies”, and his parents ultimately hired a private programming tutor for him. For 5 hours every day after school, and entire weekends, Mark would live at his computer, coding all sorts of projects and games on his IBM. One of the first games he digitized was Risk, a board game of global domination.

His other projects commonly included “hacking” AOL’s AIM messenger, which was the most popular way for teens to talk since launching in 1997. He became so natural on the computer that he would later remark that “It reached a point where it went into my intuition. I wasn’t really thinking that much about it consciously”. Hoping to bolster Mark’s chances of getting into an Ivy league and provide him with a more challenging schooling environment, his parents sent him to Phillips Exeter Academy. Despite being a very rigorous school, he was discouraged from taking AP Computer Science because he was told he knew it all already.

His senior project at Phillips Exeter Academy would be his first project that translated into commercial potential. With his friend Adam D’Angelo, Zuckerberg created a music recommendation program called Synapse.ai. He would work on this project a bit after graduation, ultimately receiving interest from AOL and Microsoft, which materialized into a $1mn+ offer. But the contingency that he work for them for 3 years made it easy to turn down. Mark would later recall, “We knew that we could do something better”. Incredibly, foreshadowing Zuckerberg’s future, another classmate at Phillips Exeter created a searchable online directory of all the students at the school with basic information for his senior project: he called it “Exeter student Face Book”. (A Face Book is a physical book of all the students that were at a school—like a yearbook, but issued at the beginning of the year for students to meet the rest of the class).

In 2002, Zuckerberg started university at Harvard College, but he still spent most of his time on miscellaneous coding projects. One of which, a gig he found on Craigslist from a Buffalo businessman to create a website, would later get him sued for claims on his future creation (the court threw out the case before prosecuting the businessman for forgery). It was typical for him to put his coding schemes ahead of his classes or coursework.

In 2003, Friendster, a social networking site positioned as “an online community that connects people through networks of friends for dating or making new friends”, was launched. Within a year, they would have 3mn registered users, including Mark. That summer, D’Angelo worked on a project called Buddy Zoo, which allowed AIM users to upload their “buddy list” (a list of people they added on their AIM messenger) to a site which would then tell you who your common friends were, as well as calculate popularity, detect “cliques”, and see degrees of separation. It spread quickly, with hundreds of thousands of users uploading their friends list. The virality of it was in part spurred by users who would upload their buddy list and then implore friends to do the same. This was Mark’s first up close experience in seeing how quickly a service can gain viral adoption and learning how the best marketing strategy is user word of mouth. A strong network grows itself. Friendster and Buddy Zoo would leave a lasting impression on Mark.

One of his first projects his sophomore year was a program he created called “Course Match” that would tell students what classes other students were taking. This tool allowed people to take the same class as their crush or take courses with friends, and it was enthusiastically adopted until it crashed Mark’s computer. From this, he gathered that “people have this deep thirst to understand what’s going on around them”.

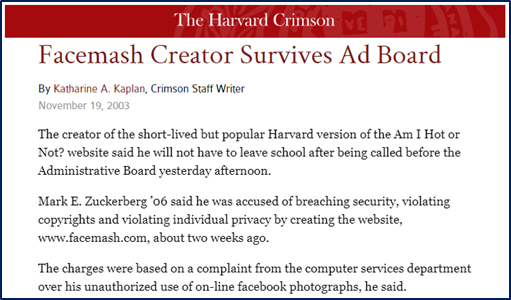

The next Zuckerberg project would ostensibly be inspired by rejection from a girl. After having a couple of beers, he went to work on creating Harvard Facemash (Oct. 2003). This program would take students’ Face Book photos from various final clubs and residential houses and show a random pair, side by side. The user would then pick the better looking of the two, a take on the popular site “Hot or Not” where users ranked people on a scale of 1 to 10. While Mark only sent a test link to a few friends, it leaked and went viral. Many were deeply offended (while others were quietly jubilant that they had ranked higher than certain peers). He had to answer to Harvard’s advisory board and was put on probation. Any future infractions would be met with increased punishment; however, Mark was already plotting another project.

The Winklevoss twins, athletic rowers who were in the upper tiers of Harvard’s social circles, reached out to Mark after the Facemash debacle. They had been thinking of creating a website that was a sort of Friendster, but only for Harvard students, called Harvard Connect (many university websites were popping up for students, sometimes created by the administration themselves. Columbia had CUCommunity, Yale had YaleStation, and Stanford had Club Nexus).

The Winklevoss twins lacked technical ability and had trouble with past programmers following through, so the site had remained unbuilt for over a year. They wanted Mark to do all of the coding to build the site in return for a vague promise that if it worked out, they would make money together. Mark had taken on various ad hoc projects over the past year and showed interest. There were various email communications over the next couple months with Mark usually indicating that he was too busy to work on Harvard Connect. (A series of unearthed AIM messages from Mark would later show that he was likely stalling working on their “dating site”, but also none of their ideas were unique--the website they described seemed like a mix between Match.com and Friendster for Harvard only with a focus on meeting people to date and get discounts to nightclubs. Of course, the decision to wait and place the entire creation of their website on a single part-time, unpaid student was their decision). Exactly what happened though would be litigated for years.

Around the same time, Zuckerberg reached out to Aaron Greenspan to learn more about his houseSYSTEM program that launched at the beginning of the school year (Aug. 2003). His app was loaded with features, including the ability to exchange textbooks with peers and even a “Face Book” feature that was similar to what Zuckerberg’s classmate at Phillips Exeter Academy had made. However, Aaron made a critical error by requiring users to sign up with their Harvard ID and the same password as their Harvard account (most likely for the email feature). Besides most students’ not trusting a random online site to take their real Harvard passwords, this decision would lead to him butting heads with Harvard IT Security, and thus the little publicity it got was negative. Aside from that, a clunky interface and perhaps too many features (job listings, a calendar, upcoming events, and email, among others) kept it from ever gaining traction. Zuckerberg would message Greenspan over AIM to talk about his creation and learn from his missteps. Mark described the many features as “almost overwhelming how useful it is” and opted for a more streamlined functionality for his project (he would also later be sued by Greenspan).

While Zuckerberg was working on his project, a Dec. 2003 Crimson (Harvard’s student newspaper) article seemed to anticipate his creation, saying that the “potential benefits of a comprehensive, campus-wide online facebook are plenty”. The Harvard administration allegedly was working on one, but few had high hopes for it.

We will never know exactly where Mark Zuckerberg got the inspiration for his next project, but it was likely a mix of everything from: 1) his early experiences watching users change AIM statuses (he built an app that alerted him when an AIM user’s status was updated), 2) seeing how D’Angelo’s friend graph took off, 3) observing peoples’ desires to stare at photos from Face Mash, 4) realizing how people want to know what their peers were doing from CourseMatch, and 6) witnessing the slew of social networking attempts bubble up and putter out. He didn’t just have any single run in with social networking, but many of his early projects all seemed to circle around what would in retrospect be his Magnum Opus.

On February 4th, 2004, Mark Zuckerberg launched TheFacebook.com.

Business History.

Going Viral.

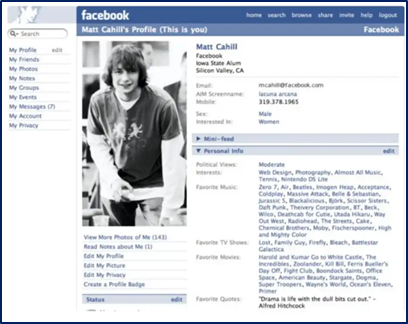

Just sending out emails to some friends was enough to have 650 students register for TheFacebook within four days of launching. Three weeks later they would have over 6,000, which was the majority of Harvard’s undergraduate population. In contrast to Facemash where his laptop served as the de facto server and easily crashed, Zuckerberg invested $1,000 in the company alongside fellow AEPi fraternity brother, Eduardo Saverin, to rent server space. With rapid growth, that would only last so long; by the end of the month, they had over 10,000 users. Zuckerberg quickly decided to extend the service to new colleges, launching each new school as standalone, closed network (Harvard students did not have the ability to look up Yale students initially).

Zuckerberg purposely chose to launch at schools that already had some kind of online Face Book site as a test to see whether or not his project was truly better. At this point, Zuckerberg was not sure if this would be an enduring creation or just another short-lived, coding fad-project like the others. Beating out Stanford’s Club Nexus, Columbia’s CUCommunity, and Yale’s YaleState gave him the confidence that this was the real deal. After seeing a rapid uptake similar to what he saw at Harvard at each of these schools, he quickly rolled it out to the rest of the Ivy League schools. Just two weeks later, TheFacebook’s user base doubled to 20,000. To keep the growth going, they decided to open up TheFacebook’s social network to cross-campus linking with the “friend request” framework: only upon mutual agreement to be friends could users see each other’s profile.

That summer, Mark Zuckerberg and several engineers moved to Silicon Valley to continue working on TheFacebook. They rented a house in Palo Alto and would code late into the nights. Business partner Eduardo (who originally put up the $1k) instead went to New York City for a finance internship. He set up a bank account and put in over $10k (along with Zuckerberg who also kicked in money) to fund their Palo Alto venture. While Eduardo was allegedly getting advertisers to help fund TheFacebook, he often came up shorthanded, and the Palo Alto team was more concerned with user growth than plastering low quality ads on the site anyway.

Eduardo started feeling threatened by Sean Parker (Napster co-founder and a well-known Silicon Valley figure), who was now living with them after a fortuitous encounter in Palo Alto. Sean Parker was slowly taking on more business functions in Eduardo’s absence, and Eduardo felt the encroachment on his job as Head of Business. Eduardo froze TheFacebook’s bank account after Zuckerberg and Parker didn’t acknowledge an email he sent that reiterated his total control of all business aspects for TheFacebook. Freezing the bank account endangered their ability to pay for servers and posed an existential risk to the company if the site went down. Mark scrambled to scrounge some funds together, including money his parents gave him that was originally intended to pay for his college tuition, and rushed to raise an angel round, something he was previously happy to hold off on.

Sean Parker arranged for Zuckerberg to meet Peter Thiel (going through Reid Hoffman), in what would go down as one of the most legendary venture capital investments of all time. Peter Thiel would invest $500,000 in an angel round for what would eventually turn into a ~10% stake (it was technically structured as a convertible note contingent on reaching 1.5mn users). As part of the investment, they would reincorporate as a Delaware company with the ability to award shares according to each person’s work contribution. Eduardo Saverin would naively sign the papers thinking it was just a formality, but it would end up allowing them to dilute him down to less than a 1% stake. (He would sue and ultimately settle for a stake that was much lower than his 30%, but still worth >$2bn at the IPO).

Zuckerberg’s messages later showed a ruthless side, saying that “I maintain that he f***ed himself. First by completing none of his three assigned tasks. He was supposed to set up the company, get funding and make a business model. He failed at all three and took the offensive against me with no leverage. That just means he’s dumb”. (The offensive Mark is referring to is the strongly worded email coming from New York and freezing the corporate bank account. While Saverin did set up a Florida LLC, it lacked contracts, governing documents, and didn’t specify the IP it owed. It didn’t help that while they all contemplated dropping out, Saverin was clear he would return to Harvard to finish his schoolwork and was openly contemplating graduate school. Saverin felt that they were living off of his largess while being the only one concerned about actually getting advertisers, which was largely true—profit was far from a concern of Zuckerberg’s at this stage of the company. In contrast, Zuckerberg fought to give Dustin Moskovitz, who they called “the ox”, for how much work he did for TheFacebook, a 5% stake.

Scaling Up.

The most important thing Thiel’s investment enabled was more servers. Facebook, as it was now called after Sean Parker’s suggestion to drop the “The”, was in a continual battle to ensure that their server capacity could keep up with their usage growth. Zuckerberg was obsessed with how Facebook worked technically, and they even added timers to every Facebook page in testing to ensure each proposed feature wouldn’t slow the page load time. By October 2004 they had 500,000 users, and before the end of the year, they hit 1mn. But Friendster still had over 15mn registered accounts and MySpace was growing quickly too, having just hit 5mn users. In contrast to Facebook’s controlled growth though, these platforms were expanding beyond their technical capabilities.

Far from a trivial factor, page load time was hindering Friendster and, retrospectively, was one of the larger factors that led to their eventual irrelevance. Users were complaining of page load times of up to 40 seconds, with 20 seconds being not unusual. Such a poor user experience was driving users away.

Zuckerberg was far more methodical than his social networking peers, controlling Facebook’s growth until their servers were ready to handle the demand. This was partly thanks to their model of launching school by school, which allowed them to temper usage in line with server capacity. Zuckerberg was keenly aware the virtues of pacing growth: poor user experience could permanently churn users away, whereas a slower roll out seemed to only be increasing demand (it was common for students to write Facebook begging for them to roll out the service at their school). Mark would quip, “I need servers just as much as I need food… if we don’t have enough servers then the site is screwed.”

Despite Friendster and MySpace towering over Facebook in terms of users, Zuckerberg never seemed to worry about them. At the time, it wasn’t clear that the use cases were really that similar: Facebook was exclusively real IDs with your real friend network. MySpace was mostly pseudonymous with most friends met online. Friendster was conceived of more as a dating site, but one where you could date more naturally as you did in real life: by meeting friends or acquaintances of others. Knowing a mutual friend provided social proof as to the mate-worthiness of a potential partner; Friendster wanted to bring this aspect online without making it explicit–something that could seem tasteless to those new to online dating (versus Match.com where strangers would meet online with the explicit intention of dating).

Whatever Friendster’s initial intention, it was wildly successful and grew to over 3mn users just months after launching (faster than Facebook). But this torrent of growth had swamped their limited systems. They had to find a new Head of Engineering, and users had to endure a site that was crippling under the load of usage while simultaneously delaying all new features and site improvements.

Friendster’s second issue was that they wanted the site to be used differently than users wanted to use it. There was a small group of accounts that were growing in popularity on the site, essentially becoming the first wave of “influencers”. However, many of them did not use their real names, which was in violation of Friendster’s operating ethos. A prominent one, Tila Tequila, was booted from Friendster 5 separate times, and each time had to rebuild her massive friend base. Rather than start over a 6th time, she joined MySpace, giving the Friendster copy-cat some traction when she emailed her prior 40k “friends”.

MySpace, which started when ReponseBase (a subsidiary of the disjointed internet holding company eUniverse/Intermix Media), was under sales pressure from their array of questionable merchandise and borderline spyware software (one scheme allowed users to download American flag cursors for free while discretely downloading a program that spammed them with pop-up ads). Chris DeWolfe and Tom Anderson would often look at Friendster with envy, noting that it was Friendster’s users that emailed new prospects, which resulted in a very high conversion rate (in contrast to ResponseBase’s email list of tens of millions that they would have to regularly spam just to get a few sales). Anderson and DeWolfe wanted to just make another Friendster, but one with fewer restrictions on users. It was hastily built and swiftly released. Only later would they notice that the site allowed users to post HTML code directly to the web page, which allowed for virtually unlimited customization; users seem to like it, so they just left it.

In contrast to Friendster, they welcomed pseudonyms and did not restrict a user’s friend count. Whereas users needed to be invited to sign up to Friendster, anyone could join MySpace. The customization, coupled with broad pseudonym usage and open registration made MySpace a sort of “Wild West” of the social networks, where anything went (it was most closely associated with safety issues early on). Similar to Friendster though, their growth would stress the platform. But they dealt with it differently. When the MySpace team noticed that a popular “degrees of separation” function was very compute intensive (it told you how many degrees of separation were between you and another user), they scrapped it. Figuring out who could see whose profile was also compute intensive, so they opened MySpace profiles up to anyone. Rather than recode the site’s workings though, they hacked it by simply adding “Tom” to everyone’s profile as their first friend. This linked everyone. They essentially scraped the idea of a social network for expediency.

MySpace continued to grow rapidly and surpassed Friendster in short order. Friendster’s issues showed up in their usage figures. MySpace would usually tout active users whereas Friendster quoted registered accounts. Myspace had roughly half of all registered accounts still active, while Friendster was closer to 1/3rd (exact figures not available). MySpace was simply more addictive, and the fewer site issues led to less users fleeing.

MySpace was aware of Facebook and had even attempted to buy them several times (Zuckerberg would receive a lot of offers to sell out and would float what he thought was an exorbitant valuation, but it seems unlikely that he would have ever actually gone through with selling). In a meeting between Zuckerberg and the MySpace founders, the MySpace founders vented about how hard it was to keep up with all the site usage and asked if Zuckerberg had the same issue. His response: “that’s the difference between a Silicon Valley Start-up and one in Los Angeles”. The quip had more than a vein of truth. MySpace would leverage the entertainment scene in LA, going to night clubs and focusing on getting bands to sign-up (they called themselves the MTV of the internet), but they always lacked technical prowess. Not only was the site slow, but they struggled to let users add more photos, figure out a working search function, or how to load videos quicker. These issues were further compounded as Zuckerberg innovated the social networking format, increasing the table stakes.

While Facebook was behind in users, the users they had were much more active than even MySpace’s. They had 65%+ of users on their site daily (some figures put that figure closer to 80% early on), and this was in an era where you had to log in through slow desktop computers.

Facebook’s differentiation of only friending people you already knew to recreate your “social graph”, or real-life social network, online was proving successful. Targeting people in college, who tend to be the most social they will be in their life, coupled with the Harvard cache and real IDs, as well as privacy from non-friends, made Facebook more trusted than any other social network. This was a critical aspect in convincing people to upload and post personal information that was never typically shared online. New features like tagging people in photos only made it all the more addictive. Facebook would also allow unlimited photo uploads versus MySpace’s capped amount. To fuel their continued school launches, they would eventually accept a $12.7mn investment from Accel Partners at a $98mn post-money valuation; what would go down in VC history as another one of the all-time greatest venture bets.

By June of 2005, they would hit 3mn users. And by October, 5mn. That was 10x their user base just a year ago and almost 1/3rd of all US college students. As Facebook would note, fighting the Friendster curse of parabolic growth degrading user experience was a constant obsession. They would spend over $4mn just on servers and networking equipment to keep the site up, an investment and priority that other competitors fumbled. MySpace, housed within a larger internet conglomerate, was constantly fighting for more server space and often resorted to stealing it from other divisions. Even when purchase orders were approved, they came in too slowly. MySpace was being crippled by the bureaucracy of their parent company (which was only exacerbated when Fox bought them), but they were still more than 4x bigger than Facebook.

2006 would be a pivotal year for Facebook. After growing at a slow and calculated pace, they would open up the flood gates with “open registration”. No longer would users be required to have a .edu email at a specific school in order to get onto the site. They first started opening up to high school students, but many high school students were already on MySpace (and it required a friend request from an existing user) which led to a disappointing uptake compared to the virtual immediate acceptance when Facebook rolled out at colleges. The relatively slower response from high schoolers led to some fears that growth may have peaked, and that Facebook would never successfully expand beyond college. It was in this backdrop that Zuckerberg considered a buyout offer from Yahoo for $1bn. While he could easily reject prior offers, he was mulling this one over. However, when Yahoo’s stock took a 20% hit after announcing earnings and insisted their offer be lowered commensurately, it was easy to walk away.

Zuckerberg had three initiatives to stoke growth: the first was an email address importer that took your email contacts and told you who wasn’t on Facebook so you could easily invite them. The second was “Newsfeed”. From watching users’ site logs, they observed that users were constantly checking all of their friends’ profiles to see what was new and if they had changed their profile pictures. Zuckerberg’s idea was to create a “newsfeed” that showed users all of these updates in a stream, ranked for what each individual would find most interesting. No longer would users have to wade through dozens of profiles to find out what’s new. There was internal backlash from the business team, who was fearful that fewer clicks would mean less opportunities to show ads. Of course, Zuckerberg won.

When Newsfeed first launched, it was immediately met with furor. Users were creating Facebook groups to express their displeasure with the change: “Students Against Facebook Newsfeed” garnered over 700,000 members (and that was just one of several protest groups). Only one in a hundred messages about Newsfeed was positive. (The irony was that the newsfeed worked so well that people found out about anti-newsfeed groups through the newsfeed). Zuckerberg insisted that people would get used to it and eventually adopt it. He was right—Newsfeed became the main attraction to Facebook in short order. He would draw on this experience in the future to support site changes despite wide user protest. Later, he would find out that this was an insufficient model to apply to all site changes, and his persistence in keeping universally unpopular changes came off as arrogant. (Newsfeed further separated Facebook from MySpace, whose tech debt was far too great and resources far too few for them to even contemplate copying the feature).

Facebook’s third initiative would be equally controversial: no longer would they restrict usage to students. With “Open Registration”, as they were calling it, anyone could now join. At the time, it wasn’t clear if this would be what made Facebook a national (or global) phenomenon, or if it would mark the beginning of the end as they lost differentiation and the necessary user trust that enabled so much online sharing in the first place.

It worked though; aided by the launch of Open Registration, they ended the year with 12mn users (Myspace still towered over them with over 100mn). Still, there were signs that Facebook users had a stronger attachment to the site than MySpace users since a higher portion of Facebook’s users signed on every day. Friendster was no longer part of the conversation, as a poor user experience and a stalling site fed up too many visitors. The same network effects that allowed it to grow so rapidly would ultimately be what lead to it unwinding (it was getting a second life in some parts of Southeast Asia though).

The next move would allow Facebook to pull further away from MySpace by adding 3rd party developers. MySpace had done this earlier, but they never developed 3rd party support and actually undermined their developers. Oddly, MySpace rolled out apps that clearly competed with their top 3rd party apps, even though there was no apparent reason to do so as they didn’t monetize well and MySpace was very strained for engineers (perhaps viewing themselves as a “media” company meant they wanted to control all content).

Facebook would instead give 3rd party apps ample support, a guide on how to make money, and near full access to users’ data (which in hindsight was a grave error). At the time, though, that meant a lot of developers flocked to build Facebook apps on their platform. The recently launched Newsfeed was an incredible customer acquisition engine for these developers, as every user who used these apps would have their activity broadcasted to their friend list. Facebook was the gatekeeper, kicking off any app that violated their terms. There would be over 25,000 apps in less than 6 months. They called this initiative “Facebook Platform”, a designation they would cherish while it lasted.

Thank you for reading! This has been an excerpt from the first part of our Meta History section. For the full history, along with in-depth analysis on Meta’s business fundamentals, market, financials, team, as well as access to our full archive of reports, subscribe below! (Or buy a single report!)

You can also check out our podcast episode just on Meta, which you can find here: Apple, Spotify