Ferrari Exploratory Report

Announcing our Ferrari Research Report!

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

In the future we will release a Company podcast episode that covers all things Ferrari, so make sure to follow The Synopsis Podcast! (Apple, Spotify).

This is a long excerpt of our Exploratory Research Report. These are reports that are about 1/3rd as long as our Extensive Research reports, but are nevertheless very comprehensive! You can get the full 34-page report by becoming a Speedwell Research Member here!

Background.

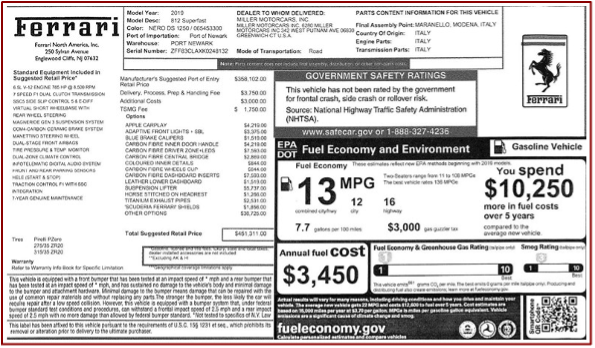

We decided to look at Ferrari given the large sell-off in shares (-35% from peak) and high quality nature of the business. They may sell only ~13k iconic luxury performance vehicles a year, but generates €7bn in revenues with 28% operating margins.

Whereas a typical car maker like Ford makes $2.5k in operating profits per vehicle, Ferrari makes $142k. The wait list for a Ferrari is 2 years, showing demand predictability that is very uncharacteristic for car manufacturers. They currently trade at 32x TTM earnings, down from a P/E ratio of over 50x.

We hope you enjoy this long excerpt of our report below!

Founding History.

A lover of motor sports racing, Enzo Ferrari started his career at Alpha Romeo as a competition driver and talent scout. Enzo wanted to directly manage a racing fleet though and in 1929 struck a partnership with Alpha Romeo. He would create a business called “Scuderia Ferrari” that managed race cars for wealthy people to compete in races.

Scuderia is Italian for “stable”, referring to a stable of horses. Thus, Scuderia Ferrari would handle all racing aspects for their rich clients and use the funds to purchase Alpha Romeo race cars. In turn, Alpha Romeo would provide Scuderia Ferrari with technical assistance. Ferrari would also try to make a surplus to attract more talented drivers who had a better shot of winning the races, so they could build a name for themselves. Enzo Ferrari pitched this to Alpha Romeo as a win for the Alpha Romeo brand if their cars won, and no downside if they lost because it was attached to the Ferrari name.

In 1933, Scuderia Ferrari became the de facto race team for Alpha Romeo when they abandoned their own racing efforts after financial troubles that led them into state control. The partnership was amended over the years, but eventually the autonomy and lack of control from Alpha Romeo resulted in them reabsorbing Scuderia Ferrari into Alpha Romeo. Predictably, Ferrari couldn’t stand his loss of independence for long and left in 1939. That same year he started Auto Avio Costruzioni because a non-compete prevented him from using his Ferrari name.

Business History.

As WWII ramped up, Enzo’s business was directed away from building race cars and instead had to help the war effort by manufacturing hydraulic grind machines. In 1943 they moved their workshop from Modena to Maranello to comply with the governments mandate to decentralize industry during the war. (This was done to spread out potential allied bomber targets.) It wouldn’t be until 1947 that the first car was manufactured with the Ferrari name, 125S. Initially, Enzo Ferrari described it as a “promising failure”.

In short while though, Ferrari was winning races and getting attention. His real passion lay in winning races, but in order to fund the racing endeavors, he knew he would need to sell cars to the public. In time they moved away from one-off production vehicles to “series production” cars, their first of which was the Ferrari 250GT in 1958. They built around 350 of these over 2 years, a huge ramp up in production for them given the highly bespoke nature of each vehicle and their small shops. The car quickly became a symbol of true wealth, status, and luxury with celebrities like Steve McQueen driving around Hollywood in one.

Despite their success in penetrating the upper echelons of society, the cost of racing weighed on the business and Ferrari contemplated an offer from Ford for $18mn in 1963. At the last minute though Enzo realized this would give Ford control over the racing budget and he stormed out of their meeting—seeding the feud of Ford vs Ferrari. Instead, Enzo turned to Fiat a few years later to buy a 50% stake, while retaining total control of the racing division. With the help of Fiat they were able to triple their production in the 1970s vs the prior decade with about 16k cars produced over the full decade. This was still by all measures an extremely low amount of production.

Part of the brilliance of Ferrari was making it purposefully hard to attain in order to build desire. An anecdote demonstrating the lore was a customer who was impressed with the cars after visiting the factory and wanted to buy one. Despite having ample inventory, Enzo Ferrari refused to sell him any on the spot, believing that: “A Ferrari must be desired. It cannot and must not be perceived as something that is immediately available, otherwise the dream is gone”. (Although, learning more about Enzo, it is also just as possible he didn’t like him as he didn’t love his customers who he referred to as a “necessary evil” in order to support their race department). Nevertheless, this practice of keeping waitlists and making customers jump through hoops to get the Ferrari of their choice was key to building the brand.

In 1988 Enzo Ferrari passed away and Fiat took their stake up to 90%. Despite the group ownership, they were able to maintain their identity and started to dominate again in F1 racing with Michael Schumacher. They also modernized their factories and focused on making their vehicles more drivable and reliable. With Enzo out of the picture, it was also easier for them to start to monetize the brand more with merchandise and licensing. In 2002 they opened the first Ferrari store.

Most impactful to the financials though was the increase in production. In the early 90s they were producing around 2k annually, which increased to over 7k by 2015. Despite this increase in volumes, it corresponded with a rising wealthy class, especially with the development of China, the Middle East and the rest of Asia, keeping demand comfortably ahead of supply.

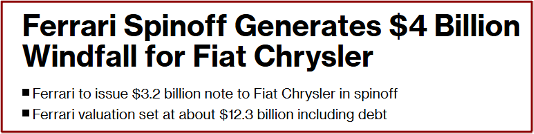

In 2015, Ferrari was “spun out” of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA). FCA sold 10% of Ferrari to the public, raising nearly $1bn, and then distributed the other 80% to FCA shareholders (the other 10% was held by Enzo Ferrari’s son, Piero. A holding company called Exor was a large FCA shareholder and currently retains a ~23.5% stake in Ferrari from the distribution). In addition to the $1bn FCA raised, they also settled Ferrari with about $3.2bn in debt.

While FCA may have talked about having Ferrari trade independently from the legacy manufacturer in order to get a higher valuation, they ultimately conducted this transaction to raise money to reinvest back into the Fiat Chrysler business, which was suffering.

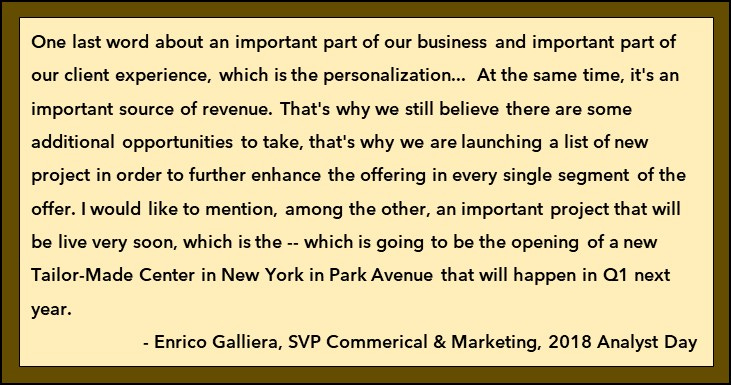

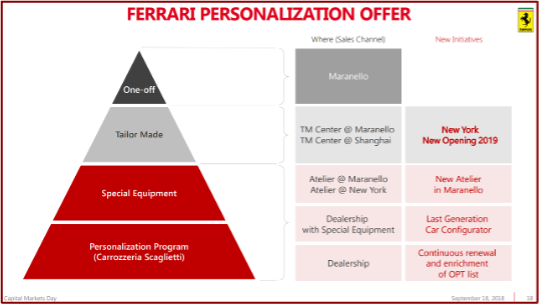

Following the spin-off, they increased their production cap of 7k vehicles annually to 10k, feeling that the market could support it and they were leaving too much money on the table. Ferrari also made a push into personalization, which could easily add another $100k to a customers bill.

In the 3Q25 earnings call they noted that personalization now represents 20% of the Car and Spare Parts revenue.

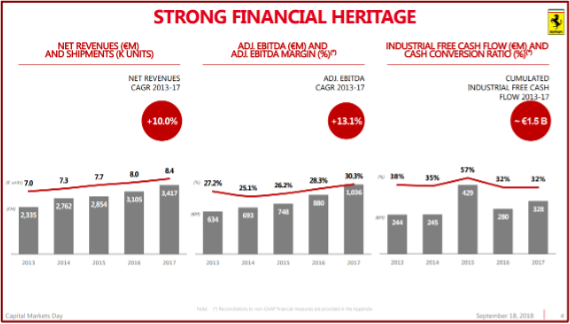

From 2013 to 2017 Ferrari grew revenues 10% annually, but increased shipments by only 5%. They set out the ambitious goal to grow EBIT to €1.2bn by 2022, about 50% higher than the €820mn they would end 2018 with.

They would end 2022 with €1.22bn (the following year they would smash this record, growing EBIT 31% to €1.6bn). Their strategy of focusing on 1) customization, 2) broadening out the models they offered—like with their first ever 4 door Ferrari, and 3) introducing “Icona” vehicles, which are very limited production, but are 5x more expensive than a “regular Ferrari”, did wonders for their financials. Operating margins moved from 19% in 2016 to 29% LTM. EBIT now stands at over €2.05bn on €7bn in revenues.

But while Ferrari still has many loyal fans—and buyers—the question is how careful do they have to be walking the fine balance between volumes and price? Is the increase in models going to eventually confuse customers and work against them? With a focus on financial performance as a standalone company, is there a risk that as they succeed financially, they risk losing the very thing that made people love them?

We will cover all of this and more below, but first we will say more about the business.

Business.

Ferrari is a leading luxury car manufacturer based in Maranello, Italy. They manufacture vehicles in-house and primarily sell them to their authorized dealership network, who then in turn sell the vehicles to the end customer. There are some exceptions for one-off special cars and track cars, which they sell directly to the end customer. At the end of 2024, their network comprised of 180 dealers who operated 200 points of sale. Ferrari does not own any dealerships, but they do have strict selection of dealers to ensure high service levels.

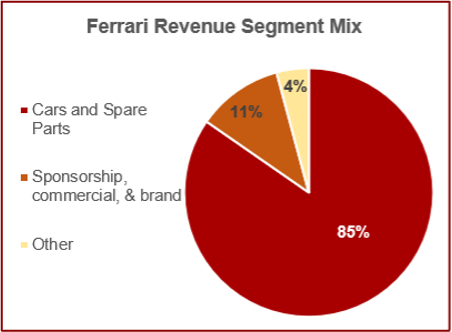

Ferrari has three revenue segments: 1) Cars and Spare Parts, 2) Sponsorship, Commercial, & Brand, and 3) Other.

Cars and Spare Parts. This segment comprised 85% of their revenues or about €6bn LTM. This has been the primary growth driver of the business, increasing revenues about 3x, or about a 11% CAGR since 2015. As the name suggests, this is where they recognize all of the car sales, as well as spare parts. Included in this segment is any revenues generated from personalizing a car.

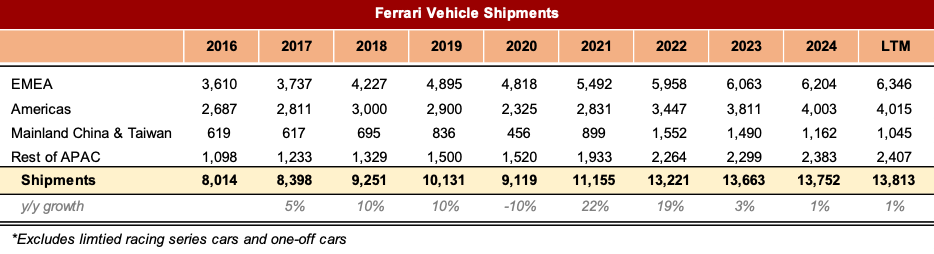

Since 2016 Ferrari has grown volumes at a 6.5% CAGR. This excludes the limited race series cars and the one-off special cars they produce. They now produce just under 14k cars annually, up from 8k in 2016. Despite this volume growth, there is still far more demand for Ferrari’s than they produce with a waitlist that generally exceeds 20 months (more on this and the “TAM” later).

This concludes the free excerpt of our report, to read the rest of the 34-page report, become a full Speedwell Research Member today or you can purchase a single report!

Ferrari Table of Contents

Founding History.

Business History.

Business.

Ferrari Business Model.

ROIC.

Valuation.

(Please reach out to info@speedwellresearch.com if you have any issues or need to speak to us to become an approved vendor in order to expense the membership).

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Members Plus also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).