How Pies, Proofs, and Punch Cards Hold Key Insights into the Cost of Equity

Reading into Commentary from Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger on Hurdle Rates

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

Intro.

Every truth requires an assumption. The Münchhausen Trilemma, also sometimes referred to as Agrippa’s Trilemma, states that it is impossible to assert any proof without appealing to an assumption. Thus, the only three ways to complete a proof are using 1) a circular argument, 2) a regressive argument, or 3) a dogmatic argument. In other words, ask any “why” question long enough and you’ll either 1) rephrase the question as an answer, 2) start repeating yourself, or 3) just give an answer that does not logically follow.

Here is a line of questioning on when is it an appropriate time to invest:

Q: When should you invest your money?

A: When you can get a good return.

Q: What is a good return?

A: Anything above your cost of equity.

Q: What is my cost of equity?

A: The rate of return required on your equity investment.

Q: What is the “required return”?

A:

Circular Answer: it’s the rate at which you should invest your money.

Regressive Answer: it’s the return that is required when making an investment.

Dogmatic Answer: it’s 10%, Buffett says so.

When to invest in a stock is perhaps one of the most important questions an investor will ask, but it also does not have a clean answer. In fact, in some very real sense, answering this question is the key job of an investor.

What is the Cost of Equity?

The Cost of Equity is typically defined as “the rate of return required on an equity investment”, but the key phrase here is “required”. Who is requiring it?

If you are an individual investor, it is yourself. If you are managing money for an endowment, they will set it. If you are managing money for a mutual fund with a mandate to be 100% invested in equities, the mutual fund investors and market are effectively setting it.

There are two distinct ways to assess returns: 1) in absolute terms, and 2) in relative terms.

While virtually every fund is forced to compare their returns to the S&P 500 (or, if you are lucky, the MSCI), most hedge funds are absolute return funds. They typically do not have the mandate to be fully invested in equity, and in fact any return they do achieve is “theoretically” less risky than the market return because they hedge their positions. A hedge fund could be considered to have done a good job even if they underperformed the S&P 500 by, say, 300bps annually, so long as their returns were more consistent.

Most individual investors are absolute return investors too, but for a different reason. That reason is that most individual investors don’t care if they beat the S&P 500; they just want to make as much money as they can. If they had the option of beating the S&P 500 by 300bps every year or making a guaranteed 9% annual return, they’d likely opt for the latter. This is not because they are doing a calculation of what they expect the S&P 500 to earn in the future, but rather because 9% is good enough. (Dear reader, you must remember by the very virtue of reading a semi-technical investment writing that you are not the average investor). In fact, most investors have no idea what their portfolio has done versus the S&P 500.

In short, if you gain no solace from knowing an index lost 50% when you only lost 40% of your money, then you are an absolute return investor.

In contrast, most long-only managers (especially mutual funds) are relative investors. They have a mandate to invest all of their capital with little exception. Their aim is to pick the best stocks from all currently available equity options. They usually do not have the luxury of waiting for better opportunities. Thus, they are relative investors because their performance is dictated by doing relatively better than an index in a given period. (While slightly off topic, it is worth pointing out that in these relative funds, the upmost important decision of when to invest is effectively outsourced to the buyer of the fund who is not looking at the current available investment opportunity set, yet is nevertheless effectively requiring they invest all of their funds).

An absolute return investor looks at what would be a good return across time while a relative return investor looks at what is the best return they can get today. This is all to say that if you are a relative return investor, the rest of this memo doesn’t apply to you—you have no choice but to invest regardless of whatever the investment opportunity set is.

If you are an absolute investor, the question of what is your cost of equity is of the upmost importance. But it’s also the wrong question to ask.

Absolute Return Investors Should Know, There is No Such Thing as Absolute.

Whenever someone is new to investing, they ask the simple, yet important question: What is considered a good investment return? If you decide not to drown them with theoretical financial jargon, you are going to either 1) pick a number a few points above the risk-free rate, 2) pick a number at or above the average historical stock market return, or 3) say the figure you believe you can generate on your stocks.

Here Psychiatrist and brain researcher Dr. Iain McGilchrist helps give us insight into why there is no clear answer:

We tend to think, for example, that there are things and then there are relations between them, some of which we make in our minds. I argue, in fact, relations are absolutely primary. There is nothing that truly exists that is not a relation.

You simply cannot answer the question of what a good return is without understanding the relationship of returns between all investments. An “absolute” does not truly exist. Could you say what makes the best basketball player ever, or only what makes someone the best basketball player relative to all who have come before?

Instead of getting lost in the theory around the right “cost of equity” number to use, we prefer a simpler and more practical idea: the punch card.

The 20-Hole Punch Card.

Buffett has a well-known quote about the 20-hole punch card where the idea is that each hole would represent a single investment, and once you hit 20 you could make no future investments.

I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it so that you had 20 punches—representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all.

Charlie Munger conveyed a similar idea with a pie metaphor in last interview:

You only get a few trips to the pie counter. If you take out of Warren Buffett's life the 10 most important trips to the pie counter, his whole record would look like dung. We knew enough to take a good helping when we were offered a trip to the pie counter.

The common interpretation is that investors should be very patient for the right opportunity and bet big when it comes. The idea also implies that only a few of their investments will represent a majority of their gains. While these are both good insights, we want to explore a different implication.

Scarcity Breeds Competency.

Looking into these remarks we can gain insight into the same question asked differently: when should you deploy capital? What the punch card framework is trying to impose is artificial scarcity. When money is more abundant than ideas, there is little stopping an investor from making poor investments with low prospective returns. In fact, most financial bubbles correspond with periods of “easy money policies” when capital is most abundant. When you have the money to do something, most people think they must do something. Listen to Munger in his interview with Todd Combs:

Todd Combs: Warren talks about the 20-card hole punch.

Charlie Munger: Oh, I love that. He said that most people would have better investment results if they got a punch card early in life that you’re very limited in investments. You’re going to get 20 investments in life and then you quit and put all of your money in cash.

The 20-hole punch card idea is about thinking beyond your current investment options to think about your opportunity costs across time. When good ideas are scarce and there is no competition for your capital, errors in judgement are likely to increase.

There is another idea in here though: your real “cost of equity” is all of your investment opportunities across time. Rather than calculating a theoretical cost of equity, an investor should think about what the investments they are likely to actually come across in their life are and whether it makes sense to keep cash on hand for that or utilize it for an investment opportunity that is currently present.

In Berkshire’s 2002 Annual Meeting, Buffett remarked on how his ideas would compete for his capital when he was more money constrained than idea constrained.

The “different equation” Buffett is alluding to is essentially that he now must pay more attention to his opportunity set across time rather than just his current opportunity set. This wasn’t exactly a new sentiment in 2002 though, as early as 1985, he was noting that they would look for a short-term opportunity if they couldn’t deploy all their capital.

But how does an investor compare current opportunities to unknown future opportunities?

Setting Standards.

Buffett has said in the past that they set their absolute minimum return threshold at 10% before tax. Otherwise, they will stay uninvested, which usually means holding short-term treasury bills. He expands on this thinking a bit below in Berkshire’s 2002 Shareholder letter.

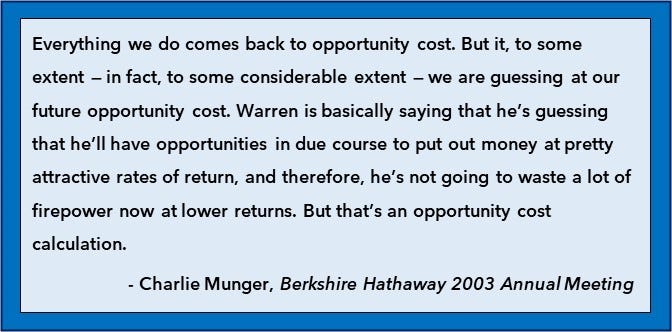

The 10% pre-tax is Buffett setting a floor on Berkshire’s required rate of return. A year later, at the 2003 annual meeting, Charlie Munger further elaborated on this idea.

A key insight is when Munger noted they are guessing at their future opportunity cost. Munger continued:

It is interesting because we usually think of required returns as an “absolute” return. That is a return that does not rely on comparison to alternatives to dictate whether it is good or not. However, where we set the threshold of a “good” absolute return is itself decided by comparison.

Aesop’s Fable is a simple story of whether someone should drop their “bird in hand” for a potential two unseen birds in the bush. As the saying goes “a bird in hand is worth two in the bush”. The Punch Card idea is essentially forcing us to remember not all birds are currently within our reach, and we may very well come across more in the bush. An investor should think of their investment opportunity set not just in terms of what they see today, but what they may ever see1.

There Will Be Periods of Inactivity.

As an individual investor, you have the luxury of not being forced to invest unless you want to be. The byproduct of this is that an investor will have a lot of cash when ideas are scarce. We typically think of cash as a drag on returns, but it is not truly a drag on returns if it enables you to invest at more opportune times.

It also serves a secondary purpose—it acts as an insurance policy and allows you to stay fully invested. Of course, getting insurance is only helpful before you need it. You least need to buy a fire insurance policy the day after your house burned down. Investors may be tempted to invest their cash in stocks with lower total prospective returns if they think they can earn more in the short term, but that is typically a foolish move for the simple reason that raising cash after a crisis is too late.

As Buffet has said, “Cash is to a business as oxygen is to an individual: never thought about when it is present, the only thing in mind when it is absent”. In The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel nicely sums up the virtues of having cash on hand:

You look and feel conservative holding cash during a bull market, because you become acutely aware of how much return you’re giving up by not owning the good stuff. Say cash earns 1% and stocks return 10% a year. That 9% gap will gnaw at you every day.

But if that cash prevents you from having to sell your stocks during a bear market, the actual return you earned on that cash is not 1% a year—it could be many multiple of that, because preventing one desperate, ill-timed stock sale can do more for your lifetime returns than picking dozens of big-time winners.

Banks borrow short and lend long. But if a bank cannot find a good investment, the most foolish thing for them to do is to “reach on duration”, which means increase the maturity of their securities to pick up some yield. Such poor balance sheet management led to the downfall of both Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic. Investors, though, commonly do the equivalent when they swap out their cash (short duration) for stocks2 (long duration) that offer prospective returns below their hurdle rate in order to deploy more capital. These investors are making the same mistake of not demanding enough compensation to lock away their money, and while it may be unlikely to bankrupt them, it is likely to lead to subpar results.

Accepting the lower returns cash brings versus longer duration investments shouldn’t be thought of as just a cost, but also a precondition for the opportunity to buy higher returning securities at more opportune times.

Here is Buffett commenting on that exact dynamic:

So what is your cost of equity?

It all of your potential investment opportunities across time.

We will be releasing a new memo every Friday morning. Subscribe below to receive it!

Also check out our podcast, The Synopsis, here: (Apple, Spotify).

Of course you can sell something to buy something else in the future. But the idea is that if you buy something subpar compared to your future options, you are likely making a poor risk/reward decision. When you go to sell that subpar investment to buy a better one, there is a higher risk you impaired capital and thus were better off if you did nothing.

Essentially all stocks have a higher duration than bonds since a stockholder never received its principal back (from the company).