If You Don't Know What Game You're Playing, You've Already Lost

How Long-term Investors Lie to Themselves

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

Intro.

It is often the case that the less specific the timeline, the easier a prediction is to make. We can predict that over some amount of time the tectonic plate that undergird Los Angeles will travel so far as to be north of San Francisco, but in any given year the distance each plate moves can vary. The Eiffel tower, owing to metal fatigue from micro movements from the wind, weather, and sun rays, will inevitably degrade without upkeep. But how much the tower is damaged in any given week is near impossible to measure within a meaningful band of confidence.

Similarly, the weather of any single day in a given New York summer is hard to predict, but we can generalize that summer is on average hotter than winter. And of course, no one can tell you what will happen any single day, month, or year in the stock market, but many would readily accept that the market will be much higher in a few decades. That is not because it is an indisputable law of physics, but rather that the factors that lead to value creation over the long-term are much more predictable than what happens in any shorter period. The more specific of a prediction you make, the larger the room for error. This is most evident with stock movements on quarterly earnings.

When Short-termism is Long-Term.

When a stock moves after a quarterly earnings report, it may seem that it is an example of short-termism, as investors use an incremental 3 months of financial information to make long-term investment decisions. A stock selling off on earnings that are just a few pennies below EPS expectations is taken as evidence of such short-termism. However, the error these investors are typically making doesn’t have to do with having a short-term mindset, but rather overextrapolation.

As we all know, a stock is simply partial ownership in a business and a business is simply worth the sum of all future cash flows discounted back to today. In theory, if no other assumptions in an investors “DCF” changed, then a 3 cent miss would only reduce the value of each share by 3 cents.

When we see a stock down 8% on a slight earnings miss, what investors are actually doing (if we are generous) is extrapolating out this incremental data point from earnings and compounding its implications across the entire future of the company. Of course, when you compound anything long enough, even small changes can have large impacts.

This is why a small change in earnings expectations can result in a large change in the company’s market value. The change in value is driven by long-term predictions, but the assumptions are susceptible to noise.

Thus, the problem isn’t the magnitude of the re-valuation, but rather the rationale. Any single quarter is only ~13 weeks of business activity and if there is just 1 atypical week for any variety of reasons, that represents an impact to ~7% of the quarter’s earnings. The market then compounds this abnormality indefinitely, leading to a huge swing in value.

Now it’s not that the incremental data point never has any long-term ramification, but rather that the data set is typically too small to reliably draw anything intelligent. Said simply, there is too much noise in a single quarter’s results.

However, string together a few quarters of similarly poor results and you may be able to see a pattern, which an investor considers significant enough to draw a conclusion from (i.e. signal). These large swings of market price could be an opportunity for a long-term investor who can parse out the difference between the signal and noise.

3-D Chess.

Unfortunately, though, it does get more complicated. There are a variety of truly short-term players that will “bet” on what others expect to happen and buy a stock with the express belief that others are over or underestimating what earnings will be for that quarter. These players are playing among themselves in a sense. Trading stock between those that think the number will be under and others that think it will be over. They hope to find a thread of data that other market participants missed, which can inform a better estimate. What a long-term investor would consider “noise”, they consider “signal”, given their shorten timeframe.

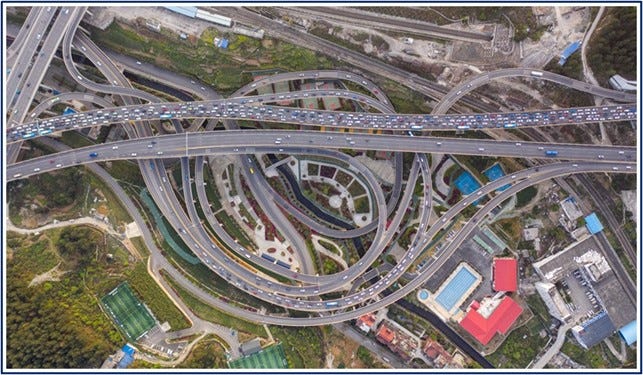

A long-term investor will neither try to predict these short-term factors, nor care much about them since they will always be a trivial portion of the company’s long-term value. But, as these short-term players, often referred to as “event-driven investors”, engage in this guessing game, a third game develops whereby other participants will bet on what others expect others to expect and so on… Now the game moves from reality to another degree, where the entire practice is predicated on expectations with a tenuous link to the real world. It would be the equivalent of instead of betting on the outcome of a basketball game, you are betting on what you think others think the betting line will be. Confused yet?

Neither the event-driven nor long-term investor is exactly wrong though: The event-driven investor focuses on perceived value whereas the long-term investor focuses on intrinsic value. The event-driven traders will not distinguish between long-term signal and short-term noise simply because that is not the game they are playing.

Playing the Wrong Game.

These event-driven players understand they are playing a different game, but much investment malpractice lies when a self-professed long-term investor starts doing the same as the event-driven investor, becoming more concerned with perceived value rather than intrinsic value.

It usually happens unintentionally or when considering career risk, whereby the investor needs an easily presentable “valuation” that they can simply and respectably conveyed in investment committees. This is how it happens.

Starting with the rationale that the future is inherently unknowable, they fall prey to a pernicious presupposition: they think that focusing on only what is easier to predict will allow them to ignore what they cannot predict easily. An investment professional, thinking they are eluding unpredictability, will value a company using next year’s earnings by taking an estimate and putting a multiple on it.

While the practice of using a multiple of earnings is well-founded, it has become so perfunctory that many investors forget it is a short-cut to a discounted cash flow model. Succumbing to the fear of not wanting to make an explicit forecast of far-out future cash flows, they instead hide such forecasts implicitly with the multiple method. (Since most businesses that are a going-concern will derive the majority of their value from earnings after ~10 years out, paying a valuation that assumes there is a decade plus lifetime is inherently making assumptions on the future).1

Essentially what these investors are saying is that they do not want to take an opinion of what the future will hold, so they will just assume every year is the same as this year, blithely missing that that in itself is a prediction! However, it gets worse! Often it is their concern with perceived value of the business that drives them to pick a given multiple and move their earnings estimates closer to what others think. This is in part driven by groupthink and the comfort consensus creates. Such an exercise turns a valuation into a guess at how others value it, or in another words a “pricing”.

Worlds Collide.

This becomes especially problematic at points of market gloom or fervor as these “long-term” investors over extrapolate in both directions. When times are full of fear, they reduce their estimates and multiples on the rationale that the adverse economic conditions call for higher prospective returns and more conservative assumptions, but in reality, it is in response to a change in perceived valued—that is what they think other will pay today and what they feel comfortable defending in an investment committee. This process is quickly reversed in better times as ebullient markets propel them to jack back up their estimates and multiples.

Much like the event-driven trader, they wind up making the same buy and sell decisions as them, but profess that it was dictated by their valuation process and not the short-term factors. As we have seen though, their valuation process often mirrors the same shortened timeline of the event-driven traders, and their lack of independence turns it into an exercise in pricing. Thus, these “long-term” investors make the grievous errors of not knowing what game they are playing, and thus they lose in both.

Four Takeaways.

There are four ideas here.

A prediction is easier to make with a longer or undefined time horizon.

It is usually foolish to change long-term estimates in response to short-term data owing to it being mostly noise.

Many market participants will buy and sell stock purposely or inadvertently looking at short-term factors.

All of these short-term participants can create opportunity for a true long-term investor, but especially in times of fervor or turmoil.

Since the factors that lead to value creation over the long-term are much more predictable than what happens in any shorter period, all the long-term investor has to do is identify attractive long-term opportunities and wait.

While the stock price may move wildly in the short-term for a myriad of reasons, the long-term value of a business is far steadier. When a long-term investor invests in a stock, they are looking to the long-term prospects of the underlying business, not the beliefs of other market participants as to what they expect the stock to trade at. They are looking to make money by buying a stake in a business and holding it as it becomes more valuable, not by selling the stake to another market participant at a higher price.

It is true that any single quarter’s earnings is an inconsequential portion of a company’s value and the fact that there are so many market participants that act as if otherwise, tends to exacerbate short-term market movements. The conflicting incentives and perverse effect of career risk can create an opportunity for long-term investors as many market participants are acting as if they are short-term investors, trying to profit from changes in perceived value rather than changes in intrinsic value.

The Antidote.

There is one last conundrum we would like to cover before concluding. How can you have confidence in the future when it is inherently unknowable, especially when short-term data points may be at odds with your long-term business assumptions?

An investor is in a privileged position for two reasons: 1) they do not have to invest in anything they do not have high confidence in, and 2) they only have to be certain of the lower range of their estimate’s confidence interval. Whenever you are thinking about a company’s future cash flows you do not need to know exactly how much the company will make, but rather can simply take the lowest estimate that you feel confident in.

In contrast, sell-side research and event-driven traders have to come up with totally accurate estimates. If consensus thinks a company will earn $22.75 next quarter and they estimated it out to be $22.60, they have failed. However, a long-term investor can simply say they think that the company will consistently earn over $20.00 and not be held to precision.

Investors cannot avoid making predictions, they can only avoid their awareness of the predictions they make.

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Plus members also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).

In fact, if you bought a company for 20x earnings that is growing EPS 5%, it would take you ~15 years to get your money back, and 60 years to make a 10% return if you didn’t want to assign “terminal value”. Even with a conservative terminal value, you still are looking at an implied business lifetime of 40-50 years.