Meta-Optimizations: Knowing When a Business is Operating from Strength or Weakness

Netflix's advantage in 2009, How Square beat Amazon, Why Ford needed a standalone EV Business, and where Gopuff beats DoorDash.

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

You can find our first Memo on the Piton Network here.

The same path will always lead to the same destination.

Preamble.

If you grant us the patience to commandeer some words and create a metaphor, we hope in return we can give you a new framework. In the words of Psychiatrist and Neuroscience Researcher, Iain McGilchrist:

Metaphor is not just a reflection of what has been however, but the means whereby the truly new, rather than just novel, may come about. When a metaphor actually lives in the mind it can generate new thoughts or understanding—it is cognitively real and active, not just a dead historical remnant of a once live Metaphor, a cliché.

Intro.

A successful business must 1) create value, 2) capture a portion of that value, and 3) protect the portion of value it’s capturing. The idea of protecting your returns is usually spoken of in terms of competitive advantages or moats and absent of them, we expect a company’s ROIC to fall to the industry average.

However, there is another source of advantage that is not exactly a moat or competitive advantage, as it is something anyone can technically replicate, but in practice no one does. This concept will also help an analyst or investor understand what competitive threats they shouldn’t fear, in addition to when a business’s new initiatives are likely to fail.

When Pitons Enable a Business.

Rewind to 2007 when Netflix decided to start video streaming. At that time, they had no expertise in video streaming, no exclusive streaming content, and no streaming customers. However, even if Disney, Paramount, or Universal decided at that time that streaming would be the future, they would have had a hard time competing with Netflix. The reason for this is simple: Disney would have never licensed their content to a Universal or Paramount platform. Additionally, if Universal or Paramount went all in on streaming, it is very likely Disney would have thought they needed to as well. Netflix’s advantage was in its weakness. Having no owned content and primarily seen as a DVD rental business, they weren’t considered a competitor, but rather a partner who can potentially help the big studios monetize their content more.

In this piece we introduced our Piton framework. A Piton is a metal spike that a mountain climber uses to anchor themselves into the mountain. They tie a rope to the Piton, which both supports their weight and limits their movement. We use the word Piton as a metaphor for:

A decision that simultaneously supports and limits the future decision space.

In our first piece we gave the following example:

If an entrepreneur decides to open a restaurant and leases out a space that has very little customer seating, they have just placed a Piton down. That Piton will constrain them from making many decisions: their lack of seating means they are unlikely to be a “full service” restaurant with waiters taking orders, since they would not be able to accommodate more than a couple guests at once. However, the restaurant’s smaller footprint also means they are paying less in rent, which together with no waiters could enable them to charge less for food. In that one decision, the entrepreneur has limited what sort of restaurant he can build, as well as what sort of restaurant he would have an advantage with.

The important point is that while anyone could have copied what Netflix was attempting with video streaming, the existing studios couldn’t. This is because their ample content library and production capabilities were a Piton: they were necessary for their core business of making and selling content, but limited them in respect to becoming a distribution pipe without a studio affiliation. (Of course, Netflix later created a studio and their own content, but this was only after they had already gained notable scale. And to the point, studios then did pull content from Netflix).

When Pitons Sub-optimize a Business.

There are many examples of businesses trying to serve a market or create a product that their Pitons do not support. Think of delivery groceries from a supermarket footprint that requires workers to traverse aisles filled with shoppers versus dark grocery markets that are configured for picking and packing. Or think of traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle manufacturers trying to enter the electric vehicle (EV) market with their existing supply chain of thousands of vendors entirely geared towards ICE vehicles. The powertrain for an ICE vehicle has thousands of parts whereas an EV has parts in the low hundreds, with almost none of them the same. (If you are doubting whether there is no benefit for an ICE manufacturer to also manufacture EVs, just ask whether you think Tesla would be a more efficient EV manufacturer if they also made ICE vehicles or if they bought a scaled ICE manufacturer like GM). If you wanted to optimize for the quickest grocery delivery possible you would need dark supermarkets, and if you wanted to create the best electric vehicle manufacturer you would need to separate out the EV business from the ICE business.

The physical supermarket footprint and legacy ICE businesses are Pitons that do not allow the grocery delivery and EV businesses to be fully optimized. This isn’t unfounded conjecture. GoPuff was founded with this idea in mind. They use dark stores as local micro-fulfillment centers that have orders ready without the delivery person having to find parking, traverse the aisles of a large store with non-uniform item placement, and stand in a check-out line. Grab in Southeast Asia has a leading food delivery platform, but also still felt it necessary to open dark stores in order to deliver items even quicker. Now, whether this is a good business is a different question; we are simply making the point that if you want to optimize for the fastest grocery delivery, you can’t use standard stores. And in regards to the ICE business holding back the EV business, Ford did recently split their EV business from their legacy ICE manufacturer, noting it was necessary to “strengthen operations” in order to compete against new EV competitors.

The key here is that a business can only fully optimize for one outcome, whether that be the primary video streaming platform, fastest grocery deliverer, or most efficient EV manufacturer. No doubt you can deliver groceries relatively effectively by sending people to pick items from Whole Foods aisles, but that will never be the fastest. To be the fastest, you need different physical infrastructure. The idea that you need to change variables in a business in order to best optimize for a given outcome we call a “Meta-optimization”. A Meta-optimization is when you optimize for an outcome with the optimal variables instead of your current variables.

If you were a baker, it is the difference between making the best cake and making the best cake using the ingredients you happen to have laying around on your shelf. You are optimizing for the variables you have versus the optimal variables to optimize for. - From our first Piton Network piece.

A Piton is a decision that both enables and limits an aspect of the business. The Piton Network is all of the Pitons that support and limit a business. How an organization is optimized today is based off of their existing network of Pitons. A Meta-optimization is when the business moves the Pitons around to best optimize their Piton Network for their value prop.

Interlocking Pitons.

As mentioned in the intro, there is a category of competitive advantages that is not exactly a moat but can deflect competitors all the same. Managers of specialty hard surface flooring realtor, Floor & Decor, have wondered why no one has tried to copy their model so far. Competitors1 are aware of their success and tried to copy aspects of their model, but one tried to copy their exact model in its entirety. They would copy aspects like directly sourcing more products or keeping more inventory in stock, but these were feeble attempts to mimic Floor & Decor’s core value prop of having the most in-stock inventory and selection at the lowest price.

Everything Floor & Decor does is to optimize for this value prop. The warehouse store allows more selection and on-hand inventory while lack of fixtures keeps the store costs low. They usually are 30-45 minutes away from most customers, which may be inconvenient, but allows them to have large warehouse locations at tenable costs. In order to use a direct sourcing model while also having high levels of in-stock inventory, they must carry a lot of inventory at their distribution centers and in their stores to account for the long lead times of ordering from overseas, which increases how much capital is tied up in inventory. Despite selling way more flooring at each of their stores than any single competitor, they actually have a much lower inventory turnover than even poorly run competitors.

All of these elements from the warehouse to the direct sourcing to carrying a lot of inventory all go together to optimize their Piton Network for having the most in-stock inventory and broadest selection at the lowest price. The interlocking nature of these elements means that a competitor cannot copy just one element and mimic Floor & Decor’s value prop, but rather must copy everything. It is for this reason that there is yet to be a copycat competitor: no one is willing to shed almost all of their existing assets in order to copy Floor & Decor.

Why are Startups Considered More Flexible?

It is for a similar reason why startups are considered more flexible and nimbler than legacy companies. In fact, a key reason why Ford broke their EV division off from the rest of the company was in order to “organize Ford to deliver… with the focus and speed of a startup”. The startup’s advantage is they don’t have legacy Pitons tying them down.

Thinking of our mountain climbing metaphor, the more Pitons a company stakes into the mountain, the more constrained they are in their movement2. If reaching the peak of the mountain was their original aim, the longer they’ve been progressing up the mountain, the harder it is to get back down and shoot for a different mountain peak.

Startups are like climbers at the beginning of their mountain climbing journey. They can pick any mountain to climb and start from any place on the mountain’s base without any Pitons constraining their movement. They can pick a path that they feel is best optimized to get them to the top. A mature company going after a new market in contrast is like a company half-way up the mountain deciding mid climb to trek a different mountain peak.

One of the conclusions on why businesses miss innovation that seems obviously within their wheelhouse is that the Pitons constrained them. Startups repeatedly outfox better resourced businesses because they start from a fresh slate with nothing tying them down. They can build their Piton Network to optimize for the new job they are trying to go after.

When a business is mature and becomes bureaucratic, there are many Pitons that have already been placed. These Pitons will dictate the direction of the organization, even if no one is consciously pushing it there. It is because of the inertia that has been built up from all of these different decisions in the past. They are each like Pitons staked into the mountain that limit the space to maneuver and make the path forward for a company essentially pre-ordained.

This all means that in order for a flooring competitor like LL Flooring to match Floor & Decor’s value prop, they have to basically start all over.

Startups Can Strike Their Own Path.

In 2014, Amazon went after Square’s market with a product very similar to Square’s credit card reader, but Amazon also added live support (which Square lacked) and undercut Square’s 2.75% fee at an introductory rate of 1.75%. Amazon also had a large marketing budget and could reach out to all existing Amazon merchants. Square was terrified that this spelled the end of their high growth, or perhaps their entire business. In response to one the world’s largest and most competent tech companies going directly after their business, they decided to do… nothing.

While Square Co-founder Jim McKelvey has his own idea on why this made sense, which he explains in his brilliant book The Innovation Stack, we think this is an instance of a larger concept.

McKelvey noticed that when creating a new business, there are typically multiple problems that must be solved, each of which tends to build off the previous one. For Square, that meant since they decided to have free sign-up, they needed a cheap piece of hardware to avoid large equipment costs with each sign up, so they designed it themselves. To keep costs low, they opted for “online-only” sign-up. This meant the sign-up flow would have to be simple and straightforward to use to avoid confusion since they couldn’t afford to build out live customer support to answer questions. Users usually expect anything online to be done very quickly, so they couldn’t rely on traditional fraud models which were slow, and since they utilized a FICO score, also expensive. So instead, they created their own fraud models. However, banks wouldn’t accept their unproven underwriting standards, so Square had to become the underwriter for each small business. In order to best appeal to small businesses, many of whom have never accepted credit cards before, they needed a simple fee structure, which was originally just 2.75%. To build trust, they would remit funds to sellers daily, a decision that is easier to make once they already bit the bullet of underwriting all of their merchants. Since they needed to design the credit card reader themselves, they had the opportunity to design it however they wanted. The design they picked was iconic and served as product awareness and helped them grow before they could afford a sales force or any advertising.

What we see is that all of these pieces came together in order to serve their small merchants with a strong value prop. The way each of these pieces builds off of the one that follows, Jim McKelvey calls an “Innovation Stack”. Edwin Land, Founder of Polaroid, noticed something similar, saying:

“True creativity is characterized by a succession of acts, each dependent on the one before and suggesting the one after”.

We want to point out though that it isn’t just with new businesses that this concept exists. It’s just as true for any company. The Innovation Stack describes the instance when all of the elements are invented, or have to be used in a new way. But the larger idea we want to hammer is that for any business, elements in that business either are, or are not, fully optimized for their value prop. Whether everything had to be invented or not, it still holds true that in order to optimize for the value prop of enabling SMBs to take digital payments, you would have to make the same key decisions Square made34

A legacy merchant acquirer couldn’t easily go after these small merchants because of Pitons they had previously placed. Their POS Terminals were too costly to enable them to give them away for free, but even if a merchant would pay up for it, it was still too complex to set up and the small volumes were unlikely to make it profitable for the merchant acquirer under their existing cost structure. Without ripping out several Pitons in their business model, from the cost of their POS terminal and the simplicity of signing up new customers to a new credit risk model and daily settlement, the legacy merchant acquirers couldn’t optimize for SMB merchants’ needs as well as Square. Preventing the legacy merchant acquirers from pulling Pitons out is the fact that it would disrupt their existing business and require them to build competencies they did not previously have.

If the Piton Network is Optimized, Competitive Responses are Unnecessary.

Now let’s go back to 2014, when Amazon went after Square with a similar product that also had live support and lower fees, which seemingly made it clearly superior to Square’s product. As mentioned, Square did nothing different in response. They were already working on live support but couldn’t accelerate their efforts, and cutting their fee rate would plunge them further into losses and make future profitability unlikely. McKelvey writes in The Innovation Stack:

“Each Square director was given the opportunity to suggest potential countermoves, and after the last idea was considered, we reached a remarkable conclusion. In response to an attack from the most deadly company on the planet we would do nothing. Precisely nothing.”

Perhaps this isn’t so odd though. Amazon itself talks about how they do not focus much on competition and instead are “customer-focused”. Many great companies similarly focus on serving their customers rather than responding to competition. If you are serving your customers, then you have nothing you need to optimize for differently. All your Pitons are placed appropriately.

It may seem that Amazon was working from a superior position, but that is not necessarily so. The fact that Amazon was also one of the largest retailers made small businesses reticent to share purchase data with them. Similar to Netflix, Square was agnostic whereas Amazon was often their largest retailing competitor. There is also the fact that since Square was a startup and Amazon a more established company, the employees at Square were very invested in the mission, whereas it was unlikely Amazon’s best engineers were tasked on this initiative, as it was a small “bet” for Amazon with minimal downside should they fail. Being a startup, Square could experiment with the design more than Amazon who created a utilitarian-looking device, and McKelvey even thinks there was an aspect that since their Square readers didn’t work well until you learned how to use them properly, it created a sort of habit and pride in merchants. It would be hard to imagine an Amazon Product Manger explaining how a glitchy device is actually a virtue that builds loyalty. Whether these are the most important reasons, or if there was another reason that is not easy to discern as an outside analyst, the point still stands that Square was already fully optimized for their SMB merchants and Amazon had many other prerogatives that had nothing to do with being the #1 enabler of small businesses to take electronic payment.

This shows that you do not need to respond to a competitor if your “Piton Network” is already optimized to serve your existing customers. Amazon could have improved their positioning with merchants by not having a first party ecommerce operation, but of course ditching that to optimize for their POS service would be a silly trade off. But this also goes to show why you should look at the Piton Network when evaluating competition.

This is most apparent when companies try to copy their competitors because there is usually something in the structure of their business that prevents them from fully optimizing their value prop as well as a more focused competitor. When a company really wants to do the absolute best it can to serve a single market, they usually have to stop doing something else. For an example, we can go back to Netflix.

Pulling Pitons out to Optimize for a Market.

When there is something new that is somewhat related, but not entirely to a business’s core activity, very seldom is it the incumbent who has an opportunity to take advantage of it. This is because the incumbent company usually has aspects of their business that are both supporting their current cash generating ability while simultaneously constricting their ability to make the changes necessary to address the new opportunity.

Again, a Piton simultaneously supports and constrains a business, and a Piton Network may be sub-optimized for the business the company is trying to build. When we see companies that usually fall prey to disruption, it seldom is simply arrogance, but rather because there is some aspect of the business model that must be jettisoned for the business to move where it needs to; however, doing so would destroy part of the company in the process.

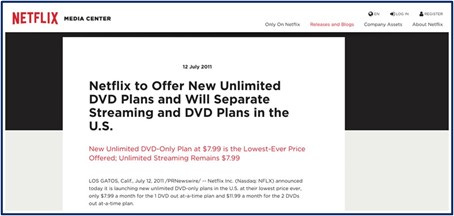

Netflix essentially cannibalized their mail order business to transition the business to streaming. Around 2011, Netflix was nearing the point that they could no longer support both streaming and DVDs under the same plan. They didn’t want the DVD business to constrain the streaming business, and so they broke the subscriptions apart and created two separate businesses for streaming and mail order DVDs. Before, a $7.99 streaming plan was available with unlimited DVDs tacked on for just $2 a month extra. Under this arrangement, the cheap DVD plan was effectively subsidizing the streaming plan. This was great to reduce churn and help DVD users build familiarity with streaming, but in order to benefit from the virtues of the streaming model with virtually unlimited scalability and a worldwide presence, they had to untie the mail order DVD business from it. The DVD business required real world operations, millions of physical disks, and is just generally a different financial model than licensing content.

As Reed Hastings notes in this interview:

“Overtime, DVD and streaming were becoming more and more different and we can do a better job for both services if we separated them… over the long term streaming and DVD are going to get more and more different. Streaming has incredible television shows. Streaming is instant. Streaming is fairly global. Streaming has many things that make it different from DVD, and overtime, both streaming and DVD will be much better because they are separate.”

While Reed Hastings didn’t say this out loud, they thought DVDs would eventually disappear and it didn’t make sense to keep investing into a dying business when they had a streaming business that required all of their capital and attention. Lastly, it was just too costly to service the DVD plans for just an incremental $2 a month. Part of splitting the subscriptions up came with a substantial price hike, one that likely pushed users who consumed both streaming and DVDs to pick one.

Users who signed up for unlimited DVDs and unlimited streaming for $9.99 a month would now be forced to choose between unlimited streaming or unlimited DVDs for $7.99 a month each (getting both would be $15.98 a month with no discount). The separate subscriptions, with no bundling, would allow each organization to optimize for their value prop individually. Netflix subscribers who originally signed up primarily for DVDs would be forced to pay for those DVDs separately. While critics reacted poorly to this decision (and especially the decision to rename the DVD operation Qwikster, a decision that was later reversed), it made sense in theory and now we can say it was a prescient decision.

At that time though, in 2011, Netflix had to endure a brutal and public customer backlash, including losing net 300k subs quarter over quarter5, which is more alarming than it sounds since the past year they added an average of ~2.5mn subs per quarter. Operating income plummeted from $376mn in 2011 to $50mn in 2012 as they started to ramp up streaming and marketing investments. Their stock price was cut 80%. If their DVD Rental business was a Piton, they pulled it right out and fell far down. But they had a second Piton—the streaming business—that would support them from then on, and they would no longer be constrained by their DVD mail rental operation.

Eventually the whole episode would be history, and, in hindsight, we can say that it was a brilliant move, if perhaps not executed with as much grace as it could have been. However, jettisoning a core aspect of your business is never going to be easy.

How the Piton Network can Predict Failure.

The Piton Network isn’t just about the Pitons a company places, but how they all interlock with each other. A mountaineer can only proceed on one path at a time, and with each Piton they strike into the mountain side, they are making a decision to move in a specific direction. The Piton Network is the sum of all of those decisions, each with certain trade-offs that together create a path, a path that is directed at only one goal. That goal is what the Piton Network is optimized for.

A Piton Network is optimized for a particular aim, and changing that aim requires going back and pulling out Pitons. Of course, Pitons both enable and constrain you, so you cannot change what the companies goals are without essentially ripping apart the business. Look at Netflix’s transition from DVD rental company to streamer, or RH going from gimmicky mall retailer to luxury lifestyle brand; these are companies that changed what their businesses were optimized for but went through immense pain to do so. Saying Google should lean more into AI at the cost of cannibalizing their sponsored link business isn’t a triviality, it requires reworking the entire business model and will likely come with a similar transition of financial pain as Netflix experienced.

From our first piece:

The Piton Network is what an organization is currently optimized for based off their existing Pitons. Too often organizations are optimizing for their current Pitons, rather than moving the Pitons into the optimal position to best serve their value prop.

Conclusion.

At the core of the idea is almost a sense of humility. Almost always, a business can only do one thing well6. The idea equally applies to your own life: how many things in your life can you truly optimize for at once?

In cellular biology there is a concept called pluripotency. A pluripotent cell is one that has full capacity to differentiate into any sort of cell, but they must become only one type of cell. Cells that are only partially differentiated are usually referred to as “cancer”. Similarly, a company that tries to become too many different things at once is serving nothing well and may as well be cancerous.

Podcast.

For more business insights check out our podcast, The Synopsis.

Follow us on Spotify, Apple, or where ever you get your podcasts.

Lowe’s ran an experiment to copy Floor & Décor, but they never fully committed to having a full warehouse store dedicated just to flooring. As such, their attempts to copy them were relatively feeble from the outset. Home Depot in contrast did have a flooring only store and their decision to abandon it likely had less to do with it being unsuccessful and more their need to conserve resources in the midst of the great recession. It is unclear why they never revisited this idea though.

We are aware that we are stretching the metaphor, and a climber would not be attached to multiple Pitons at once. We are trying to convey an understanding and are happy to trade-off an accurate description of how climbers actually climb mountains in order to get there.

In the first piece we referred to “load-bearing Pitons” as those that a business must build off of in order to fully optimize for their value prop. Floor & Decor’s load-bearing Pitons are the warehouse model and directly sourcing.

The Innovation Stack describes the instance when a company has no Pitons and can create a business that is perfectly optimized for their value prop. Since most startups are doing something new, they end up needing to create many elements in order to best optimize for their value prop. By virtue of the startup having no elements or Pitons means they can focus on just optimizing for their value prop whereas a legacy competitor would have to try to serve that value prop from their existing Piton Network, which almost always is a sub-optimization.

From the quarter ending June 30th 2011 to Sep. 30th 2011 total unique subscribers fell ~300k

While there are some exceptions like Amazon with AWS, even in that case Bezos was clear that AWS should be treated as its own standalone unit without any special integrations or APIs. The retail business didn’t support AWS and in fact they weren’t even their original customer as it took them a long time to port everything over to AWS.

Classic response to innovator 's dilemma is to spin up value propositions that serve evolving consumer JTBDs. Pitons or no pitons -