Porsche Exploratory Report

Porsche AG Company Exploratory Research Report

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

We will also record a podcast episode on Porsche soon, follow our podcast here to get it when it’s released: (Apple, Spotify).

This is an exploratory research report, which means it is about a quarter of the depth of our typical reports. The idea of these pieces is to do preliminary research on a company or industry before we decide to do a full deep dive that requires many hundreds of hours of research. That means that we will most certainly overlook certain aspects of the business. While it is our intention to get a reasonable understanding of the company and industry, since we are not doing our full multi-week research process, these pieces are likely to have some omissions. However, they should still be helpful in getting a reader exposure to new industries, businesses, and ideas. These pieces also may serve as a launchpad for a future full deep dive.

Business History.

Ferdinand Porsche was known for being a very creative and talented engineer. He created the first hybrid car in 1901, then led the design and production teams at a number of car companies for the next few decades until deciding to work for himself.

In 1931, Ferdinand Porsche, alongside Anton Piech and Adolf Rosenberg, founded Porsche, or, more exactly, “Dr. Ing. h. c. F. Porsche GmBH”, in Stuttgart, Germany. The company’s name is a German acronym for “Honorary Doctor of Engineering, Porsche, Design and Consultancy Company for Engine and Vehicle Production”.

Unsurprisingly for a German manufacturing business that operated during the Nazi regime, they have a checkered past. (Jewish Co-founder Adolf Rosenberg’s stake was “bought” out by Ferdinand for a pittance after the Nazi’s rise to power to complete “Aryanization” of the company.)

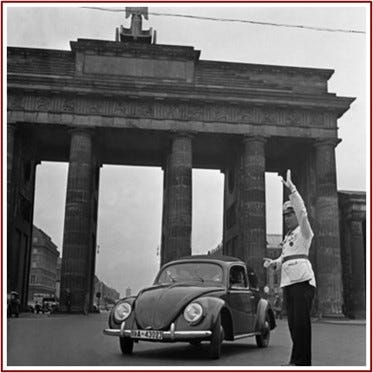

Adolf Hitler’s early initiatives included building out a road network and a focus on creating a “people’s car”. Hitler tasked Ferdinand Porsche with helping design the vehicle. Hitler then founded a state-created company in 1937 called Volkswagen, which translates to “people” and “car”. Porsche’s first big break was successfully designing what became known as the Volkswagen Beatle. Ferdinand himself was also tasked with overseeing the creation of the Volkswagen plant.

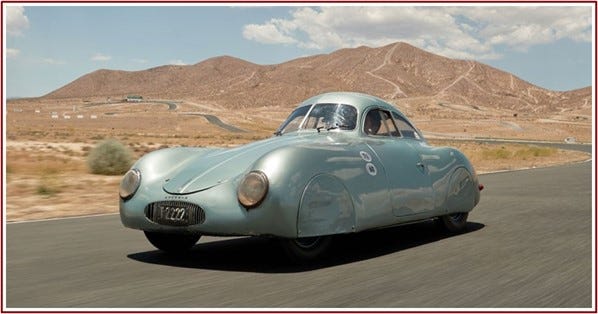

At the same time, Porsche continued with consultancy work on race cars. One such project resulted in the Type 64, which was also called the Porsche 64, and a direct predecessor to their later sports car. As World War II raged on, their efforts shifted to designing and helping manufacture vehicles for the German war effort. After the war, Ferdinando was briefly imprisoned by French authorities for his role in the war, and his son, Ferry Porsche, took over running the company. It wasn’t until several years after the war that Porsche was able to return to focusing on sports cars.

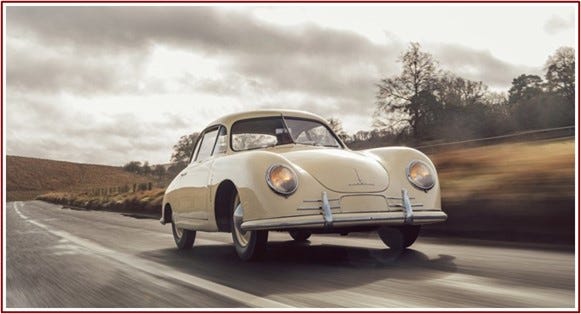

Sports cars became the center of what Porsche is today after they designed what would become their first production run sports car, the Porsche 356. At the time, Ferry said, “I couldn’t find the sports car of my dreams, so I built it myself”. The first 356s were sold in 1948.

The idea behind the car was simple: instead of putting a large engine in a large car, it would be a better driving experience having a small-sized engine in a small car. Additionally, the smaller engine could be housed near the rear, which put more weight towards the back of the car for better balance. The lighter weight would make up for the lack of power, but would result in improved handling, allowing better cornering.

It wouldn’t be until 1965 that they replaced the 356 with the car model that has since become synonymous with Porsche: The 911. The 911 quickly became a very popular sports car and would carry Porsche for decades to come. Throughout their history though, they would retain a partnership with Volkswagen, with various design, manufacturing, and distribution agreements.

On the heels of their success, in 1972, Porsche went public on the Frankfurt stock exchange. (We will touch on the current and confusing corporate structure later). Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Porsche faced a tough business environment. High oil prices from the oil embargo crisis, emissions regulations, and a lackluster car lineup pushed customers away from Porsche.

In the early 90s, the glow of the 911 was wearing off, and alongside a strengthening German Mark (making the car more expensive internationally), the company was struggled financially. Sales fell from over 50k vehicles in the mid-80s to just 14k in 1993. They were wasting money developing and supporting cars like the 928 and 968 that weren’t big sellers while the 911 was still their only “hit” model at the time.

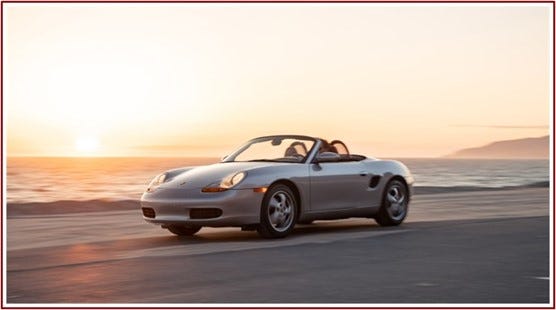

This changed in 1996 when they relealed the Porsche Boxster. Despite gaining wide popularity as the “poor man’s 911”, the Boxster alone would generate almost the same amount of vehicle sales in a single year as the entire company did at its weakest in the early 90s.

While the company was financially improving, they were still essentially a niche sports car manufacturer. They certainly had a loyal and devoted fan base, but they were manufacturing a fraction of the cars their German counterparts were with production numbers around 50k vehicles versus Mercedes-Benz at 1.1mn at the turn of the millennium.

The limitations of growing Porsche’s volumes were simple: they only sold two-door sports cars. To change this, in 2002, they took a gamble and released a Porsche SUV—the Cayenne. While some enthusiasts would roll their eyes at the defilement of the racing heritage of the Porsche brand, it sold extremely well. They led the way by creating essentially the first luxury SUV and reaped the benefit of being first to market. In just one year, Cayenne unit volumes were almost twice that of the 911 and continued to grow from there.

In 2008, Porsche reached further into making cars for everyday use with the 4-door Panemara sedan. While not as popular as the Cayenne, it still sold on par with the 911 line and added further diversification to their lineup. Volumes continued to grow to almost 100k in 2007 before the global financial crisis sapped demand for luxury cars. Volumes would fall 22% in 2008 and then slowly creep back up to reach a new high in 2011, then continue to grow by ~20k incremental vehicles each year.

In 2014, they launched the Macan, a crossover SUV, which proved to be on par with the Cayenne in popularity. With the exception of 2020 due of Covid distortion, they grew volumes every year. In 2022, Porsche AG returned to public markets at a market cap of nearly €78bn with revenues of ~€38bn and earnings of ~€5bn.

With 320k units produced in 2023, can Porsche maintain its high-end image to hold onto its premium pricing? China represents a material portion of volumes at 25% today, but that has been shrinking the past few years. Can volumes continue to grow through this headwind? When Porsche originally launched their SUV in 2002 they were an early entrant. But now, high-end SUV competition comes from Aston Martin, Audi, Bentely, BMW, Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, and Mercedes-Benz, among others. Will competition weigh on demand? And this is before mentioning the biggest trend in the automotive industry in decades: the electrification of cars. Not only do electric vehicles require building entirely new vehicle platforms, but it presents an opportunity for new competitors to enter the industry. How will all of this shake out?

We will touch on all of this and more in this exploratory report on Porsche. We will start with some background on the corporate structure and then move into the business.

Corporate Structure Background.

The IPO in 1972 we mentioned earlier was that of Porsche AG, the car company. However, in 2007, Porsche formed a holding company called Porsche SE, and put their 100% ownership of Porsche AG in there. They then issued debt at Porsche SE and used the proceeds to attempt to take over Volkswagen (VW). By 2008, they had a >50% stake in VW. The financial crisis changed their plans though. Instead of a takeover of VW by Porsche SE, the overlevered holding company Porsche SE couldn’t sustain their debt load. In a twist of fate, Volkswagen acquired a 49% stake in Porsche AG, and later acquired the other 51% to make it a wholly owned subsidiary. At the time, Porsche SE still owned their controlling Volkswagen stake, allowing them to effectively maintain control over Porsche through their Volkswagen ownership.

In 2022, to unlock shareholder value, Volkswagen IPOed Porsche AG. Porsche created two classes of stock: ordinary shares and preferred shares. The preferred shares would have no voting rights but would be entitled to an extra €0.01 in dividends. Their total shares outstanding (ordinary plus preferred) was set at 911mn, split evenly between the ordinary and preferred. In connection with the IPO, Porsche SE acquired a 25% plus 1 share stake in the ordinary shares of Porsche AG, giving them a blocking minority vote. The rest of the ordinary shares were retained by VW.

The IPO was for 25% of the preferred shares, which, since the preferred shares are only 50% of the total shares outstanding, represent 12.5% ownership in the company. Including the stake sold to Porsche SE, VW raised €19.5bn in IPO, half of which they retained to invest in the electrification of their vehicles, and the other half being paid out as a special dividend. At the time of the IPO, the valuation of Porsche AG was €78bn.

Business.

Porsche is a large automobile manufacturer that produces a variety of high-end internal combustion engines (ICE) and electric vehicles (EV). The Porsche Group’s revenues for 2023 was €40.5bn, split between their automotive and financial services segment. The automotive segment is the vast majority of revenues at 92%, which we will dive into more below.

The other 8% of revenue comes from their financial services segment. Their financial services are primarily from their leasing businesses, dealer & customer financing, and service & insurance brokerage businesses. In select markets, these services are also offered for other Volkswagen brands, primarily Bentley and Lamborghini.

The automotive segment, which represents €37bn in revenues, could be further broken up into revenue from 1) vehicles, 2) parts, 3) used vehicles and 3rd party products, and 4) other revenue. Vehicle sales make up the vast majority of automotive revenues at 84% or ~€32bn. Interestingly, the other revenue includes consulting revenue as the Porsche Group owns two consulting firms: MHP Management with >4,500 employees, and Porsche Consulting with just <1,000 employees.

In 2023, they delivered 320k deliveries with the Macan and Cayenne models the most popular. Notably, they also continued to grow 911 volumes, which reached 50k in 2023. The all-electric Taycan is the newest member of the Porsche family, which grew from <1k units in 2019 to 41k in 2023. They will release an all-electric vehicle based off of the Macan in the back half of 2024.

In the past five years, total volumes have grown at a 2.6% CAGR. Most of the volume gains come from the launch of the Taycan and the expansion of 911 production. The average selling prices of Porsches have grown to €117k, which is up from €100k in 2021 and €93k in 2019. That comes out to about a 4.7% 5-year CAGR.

In 2021, the Porsche Group generated €5.3bn in operating profit on €33.1bn of revenues representing a margin of 16% margin. In the past two years, margins have expanded 200bps, with them earning €7.3bn of EBIT on revenues of €40.5bn for an 18% margin. However, included in IFRS “operating earnings” are several non-operating items such as forex gains, derivatives, and asset disposals, which net out to ~€330mn in 2023.

Industry.

The global automotive manufacturing industry is estimated to be valued around ~$3tn. It’s massive economic impact, large technical workforce, sizeable industrial manufacturing capabilities that could be decisive in a war, and nationalist pride for having domestic-built cars have made the automotive industry a harbinger of protectionist policies and subsidies. The fight for a healthy domestic automotive industry means foreign vehicle manufacturers can be disadvantaged. China has a 15% tariff on foreign vehicles, which they may raise to 25%. The EU has a 10% import tax with higher rates for Chinese-made EVs. The US enacted a 100% tariff on Chinese-EVs and passed legislation to subsidize the purchase of US-built EVs. India recently had up to 100% tariffs on EVs, which they lowered to 15%. All of these policies are aimed at shoring up each country’s domestic automotive industry while also helping them lead in new technological advancements like EVs.

This creates a lot of distortions from a business perspective. It impacts where a company may decide to build a vehicle, where they can sell the vehicles, and what types of vehicles they should focus on. The real problem though is that automotive company investments are in physical assets that cannot move and take many years before they can accrue any economic gain. Politics, in contrast, can change rapidly, which puts each car manufacturer at risk of being caught wrong-footed against certain legislation.

In total, there are around 85-95mn new vehicles that are manufactured each year. Of these, about 20-25mn are commercial vehicles. Very large vehicle manufacturers like Toyota or Volkswagen, respectively, make 11mn and 9mn vehicles annually. High-end car companies such as BMW and Mercedes-Benz make over 2mn each. Luxury vehicle manufacturers like Ferrari and Lamborghini make in the vicinity of 10k cars a year. Porsche sits somewhere in the middle between BMW and Ferrari, with 320k cars produced in 2023.

Since cars are durable goods, their replacement can usually be deferred for some period of time. This, coupled with the fact that a car purchase is a meaningful economic decision, means vehicle volumes tend to be volatile. In 2017, 73mn vehicles were produced globally, which was 9% higher than in 2019 (and this is well before Covid’s impact). While it may not seem like a large swing, that is still a difference of 6mn cars. Given the multi-month lead time it takes from receiving an order to having a finished vehicle built and delivered to a dealer, estimating demand accurately is extremely important. Produce too many vehicles and your capital is stuck in inventory that depreciates (older model cars are worth less than newer models) and you may be forced to discount cars. Produce too few cars and a would-be car buyer may wind up with a competitor’s vehicle instead.

Managing inventory is only made worse by the vast variety of different car models and combinations of options. Its not just about producing the right number of cars, but the right number of compact 4-door sedans with a small engine block, the entertainment package, and sports wheels in dark blue. It is especially tricky too because consumer preferences vary wildly.

One customer might be dead set on a red car and couldn’t care less about the fuel efficiency, while another customer is buying almost purely off of the highest Miles per Gallon. The car manufacturer needs to know not only how much to produce of each car, but what aspects to focus on in the car in the first place. Automotive history is littered with examples of vehicles that were produced with no market for them (anyone in the market for a sports convertible pickup truck?)'

Misses can be more subtle though. Perhaps a manufacturer focused on creating their own infotainment system instead of just using Apple’s CarPlay which was enough to push a would-be buyer to a competitor. However, car manufacturers with strong brands and legacies like Ferrari or Lamborghini do not have to play this game. This is because a Ferrari buyer first and foremost wants a Ferrari. They do not care much about CarPlay, cup holders, or cargo space. There may be alternative luxury sports cars, but there is no alternative “Ferrari”, and many Ferrari-enthusiast will not be satisfied with other brands.

This is the best position a car manufacturer can be in because they are not really competing against other manufacturers for sales. Ferrari decides what they want to make and has no problem selling the full lot of production. In fact, there are usually waiting lists for most models. This eliminates the largest pain point for most car manufacturers: estimating demand. This is because Ferrari is fulfilling a consumer preference that no other manufacturer can fulfill: owning a Ferrari.

In contrast, Toyota must make enough Camrys or risk losing to Honda’s Accord because their buyers first and foremost want a decent, affordable car with some amount of features like electric windows and air conditioning. These are all preferences though that any car manufacturer can fulfill. This is the most competitive area of the car market, and since there is little proprietary about what ends up in their cars, most manufacturers essentially compete on price, making production scale key to winning.

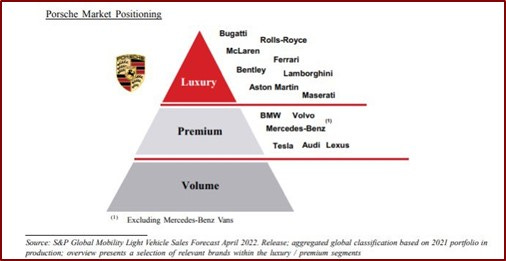

Porsche is unique in its positioning. While it is far from Ferrari, it also can’t be grouped with BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Audi either. The average consumer places Porsche above the BMWs of the world and below the likes of Bentley, Rolls Royce, Aston Martin, and Lamborghini. This is in part because of their strong racing heritage and brand that was built from the 911 sports car. As Porsche has continued to build their line out with more everyday cars, they are arguably diluting the brand image, but it has been done responsibly enough that Porsches are still desirable.

It is a careful balance between making vehicles scarce and desirable and monetizing the brand with more cars and models to sell. The creator of Ferrari, Enzo Ferrari, had to balance the same prerogatives. He wanted Ferrari to be solely a race car company and winced at the idea of creating watered down road cars for the general public. Nevertheless, their road cars arguably helped build the brand with Ferrari becoming a desirable car that celebrities and millionaires drove. More recently, it was thought that a 4-door Ferrari would materially ruin the brand. But there hasn’t been a noticeable difference in the prestige of the brand since the Purosangue was announced. Short of being reckless with their image, a high-end brand tends to have a lot of goodwill among consumers that gives them flexibility in how to monetize.

Among car enthusiasts, Porsche and Ferrari are often compared together because of the racing legacy. Porsche after all has won Le Manns 19 times versus Ferrari’s 11, and both maintained a performance-driven culture. The 1971 film Le Mans starring Steve McQueen further crystalized the Porsche vs Ferrari rivalry in the minds of many consumers. It is a common question among sports car enthusiasts if they are a Ferrari or Porsche lover. This brand cachet has continued to grace Porsche despite the launch of a several everyday cars that attract everyone from white-collar workers to affluent soccer moms.

The difference between premium and luxury can be debated, but generally it is thought that with a premium product you are getting something material in return for the higher price. A better engine, nicer interior, and improved handling are all things that warrant a premium price. However, when you pay a higher price simply because of the perception of the product and more ineffable aspects, like the feeling it brings you, then you are entering luxury territory.

In 2009 for example, the Nissan GT-R beat a Porsche 911 Turbo and even a Bugatti Veyron for a faster lap time around the Nurburgring, a popular racetrack in Germany to test a car’s performance. Nevertheless, the Nissan GT-R’s MSRP was around $80k. As the price suggests, no one was willing to pay a premium because it was a Nissan or a “GT-R”. What the buyer was paying for was performance.

In contrast, it is hard to justify the Bugatti Veyron’s $1.7mn sticker price (in 2009) in terms of what you are getting for your money. There is clearly a prestige, scarcity, and luxury aspect that you are paying for. The Porsche sits somewhere in the middle, closer to the Nissan with an MSRP of $140k at the time (a Ferrari F430 had a base price of $220k back then).

Looking at gross margins we can get a sense of how much a premium Porsche garners versus competitors today.

While there is definitely volatility in these margin figures, we can see that our general intuitions are backed by these figures. Ferrari has by far the highest gross margins, followed by Porsche and then Mercedes.

Porsche Business Model.

Porsche’s model is to build prestige and performance excellence with their flagship 911 sports car, as well as limited models like the 918 to garner attention and ensure they are continued to be talked about in the likes of other sports and super cars. The point is to make sure Porsche is still in the conversation next to Ferrari, Lamborghini, McLaren, etc. While this is key in itself for them to sell sports cars, this association with other more expensive manufactures is also what supports their high-end brand image.

Porsche then extends this brand image to different models that have more consumer demand like SUVs and sedans. They are selling a “sports” version of a typically non-sporty car. While other manufacturers have certainly moved to do something similar, Porsche is in a unique position. They have the racing heritage and brand to be mentioned among the likes of Ferrari, while also producing volumes closer to the scale of a large car manufacturer. In the last year alone, Porsche’s volume growth was almost more than Ferrari’s entire annual production. Despite churning out hundreds of thousands of vehicles a year, they still maintain an allure that puts them ahead of other premium vehicle brands.

This purgatory-like positioning between “luxury” and “premium” is shown well by our survey below (N=311). While premium was the most common answer, 59% of respondents thought of Porsche as higher than “premium”, and a third considered it a luxury car.

The Porsche production formula is essentially to keep this balance. They will avoid producing so many units that the brand slips to be on par with BMW, but they also have no interest in throttling their sales to maintain an undisputed luxury image.

The decision between maintaining higher prices or increasing volumes is a well-known trade-off for many businesses. In this piece we talk about the two ends of the sales spectrum and in this piece we introduce The Value Capture Index.

The idea behind the index is to essentially answer the question of how much does inventory turnover need to increase to offset a lower margin. This gets at the key volume vs price trade-off many businesses face. (The calculation is operating income over average inventory. The idea is to see how well each business monetizes their inventory. See here for an explanation).

Below we show gross margins and operating margins of various peers. As expected, Ferrari comes in the lead with 27% operating margins versus Porsche at 18%. We see GM and Ford at the other end with low single digit operating margins.

Ferrari has a very incredible inventory value capture index score of 2.0x, which means for every dollar of inventory they hold, they can turn it into an operating profit of $2. Porsche is also quite high at 1.3x. It is worth noting the magnitude of difference between average inventory between the two though. Ferrari carries under €1bn in inventory on average, whereas Porsche carries more than 7x that. There is little chance Ferrari would be able to monetize their inventory as well as they currently do if they had to produce ~7x as much, suggesting that Porsche is making a fair trade off of margin for total profit dollars.

We can see that Mercedes-Benz has even more inventory (includes their vans division), but has a similar inventory turnover ratio to Porsche. However, since they have extended their brand so much, they cannot demand the same price premium Porsche gets and thus their margins are lower and inventory value capture index is 0.7x.

Tesla is an interesting data point as well because before their price cuts, they were operating at a value capture index of 1x and their operating margins were 17%, nearing Porsche’s despite delivering 1.3mn cars vs Porsche’s ~0.3mn. (While there were exogenous factors from the supply chain shortages giving all car manufacturers more pricing power and EV-specific subsidies that could have played into this figure, it does suggest that Tesla could have a unique model versus other competitors. This is a topic for a different piece though).

Interestingly, Ford and GM, who have the highest inventory turnover by far, also have the worst monetization of their inventory. Despite GM having $16bn of inventory on hand, they sell it all every 40 days. This is an incredible amount of sales that helps make up for their tiny profit margins, giving them a value capture index score of 0.6x. We see here two different formulas for monetizing inventory: the first is Mercedes-Benz which turns inventory 4.7x with an operating margin of 13% and the second is GM which turns inventory 8.9x with an operating margin of 5%. Both strategies yield to a similar monetization of inventory.

Given GM’s high turnover, we would expect them to focus more on volume and market share. We can see their focus clearly in the third page of their annual report, which gives market share stats by geography. This is what you would expect from a mass producer of automobiles across a variety of brands. However, market share focuses typically come at some cost of profitability, which we also see with GM.

The Porsche model is keeping their volumes at a level where they can still garner a premium price, but not holding back on production so much that they leave a lot of potential sales unfulfilled. Instead of just taking pricing up, they tend to try to emphasize mix shift towards higher end models like their “S” and “Turbo” versions. It is a delicate balance, and their financials suggest they have been good at it. However, if there is a degree of brand dilution occurring, it won’t be known for many years, and likely until it is too late to reverse.

ROIC and Unit Economics.

Looking at the ROIC of the consolidated company presents some problems. We can calculate their ROIC on a NOPAT basis, but that overstates their cash earnings as their capex tends to run higher than their D&A and R&D expenses (they capitalize a portion of R&D). For this reason, we would want to look at free cash flow. However, Porsche’s captive financing subsidiary creates their own distortions on the cash flow statement…

Become a Speedwell Member to get the rest of this report.

If you are a Speedwell Member, click here to read the rest of this post.

If you are not currently a Speedwell Member, but wish to join, click here.

Thank you for reading the sample of our Porsche Exploratory Report! Become a Speedwell Member today to get access to the rest, as well as gain access to our growing library of Extensive Research Reports.

Members can read all of our reports on CSGP, CSU, CPNG, CPRT, DFH, ETSY, EVO, FND, META, RH, and WD so far!

*At the time of this writing, no contributor to this report has a position in Porsche. Furthermore, accounts that one of more contributors advise on do not have a position in Porsche. This may change without notice.

The Synopsis Podcast.

Check out our podcast for more business and investing content. We will dedicate an episode to Porsche on it soon! In the mean time, you can find many company-specific episodes on other businesses we have written about.