The Risk Circle: Deciding What Risks Matter and When

Solar Flares, Aswath Damodaran, 75bps 2022 Fed Funds, The Pentagon Papers, Buffett's Washington Post Investment

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

Willful Blindness.

All investments require making many assumptions. It is usually an investor’s job to distill the investment thesis down to just a few assumptions. However, that does not change the fact that there are hundreds of hidden assumptions in every thesis.

These assumptions span from the highly probable, such as the United States will continue to be a sovereign nation capable of protecting property rights of business, to the highly improbable, such as the magnetic poles will reverse again for the 180th odd time, making North South and South North and causing all sorts of unknowable havoc on every electric and magnetic system in the world simultaneously. However, you would never expect an analyst to list “magnetic poles flipping” as a risk on their investment.

What if the previously calculated risk of an X-class solar flare (the strongest) is three times what we previously thought? Do we adjust the equity-risk premium? If aliens visited us tomorrow, how much should the risk-free rate move? These questions are meant to be ridiculous, but they are ridiculous because we all have a deep-seeded belief that a certain category of risks should be excluded when investing.

While in the scenarios above most people would not argue that the discount rate should be adjusted, there are risks that reasonable people may disagree on whether they should be included or excluded from The Risk Circle, that is the list of risks you demand to be compensated for. Should we dismiss someone who worries about the increasing likelihood that the US dollar is no longer the reserve currency and not think through the potential adverse impacts? How much of the “American Economic Miracle” was a byproduct of this one factor? Our $33tn in federal debt and $1tn+ annual deficit is certainly a luxury no other country in the history of the world has been able to afford without being the dominant currency. At what point does this become worrisome, if ever? How do we decide what risks to ignore?

Instead, we all create a sort of mental circle of “prosaic” risks and only focus on those. We usually just ignore the millions of very remote probability things that could render an investment worthless. Buffett is explicit about part his circle when he notes that you do not bet against America. He basically does not consider any risk in his investments that the United States capitalistic system stops working so well. Fair enough, as the United States has not only created one of the greatest growth periods in standard of living and innovation the world has ever seen, but has also survived several periods where anti-capitalistic ideologies like socialism gained prominence. Almost all of his investment success is predicated on the “American Miracle”, which itself was reliant on a myriad of conditions to occur. But he doesn’t spend all of his time (or any?) worrying about what could bring about the rise of socialism in the United States.

Quicksand Used to Just be Sand.

We are all going to die. This is a biological fact1, and yet most people spend little to no time thinking about it. In fact, if you spend too much time thinking about it, then people would say there is something wrong with you (thanatophobia). There is a category of risks that are the equivalent of this. But there is a small spot where risks move from being out of The Circle to entering it. When this happens, markets can react violently. While the risk of the Chinese government pushing private enterprises to make decisions that weren’t in shareholders’ best interests was ever present, over the course of just a few months, the market started to weigh this risk much more seriously (MSCI China is down ~60% from peak… still). If this risk was always being priced accurately, then there likely wouldn’t have been such a violent repricing (of course, everything is multifactorial).

The risk of inflation, and the higher interest rates it could bring, was also initially ignored. In November 2021, the WSJ published an article titled “Inflation Data Fuels Climb in Short-Term Treasury Yields”, and despite the core CPI at 4.6% and increasing, the market arguably ignored the risk that inflation would cause interest rates to hike. At the time, the futures market was only pricing the chances of two rate increases by the end of 2022 at 80% and the chance of 3 rate increases at 49%. The stock market wouldn’t peak for nearly two months after this article was published.

While it made sense given most investors’ experiences with inflation over the past three decades (none) that they would not typically include inflation risk in their Risk Circle, even when evidence started mounting, by and large they still continued to price stocks as if the Fed Funds rate would stay near zero indefinitely.

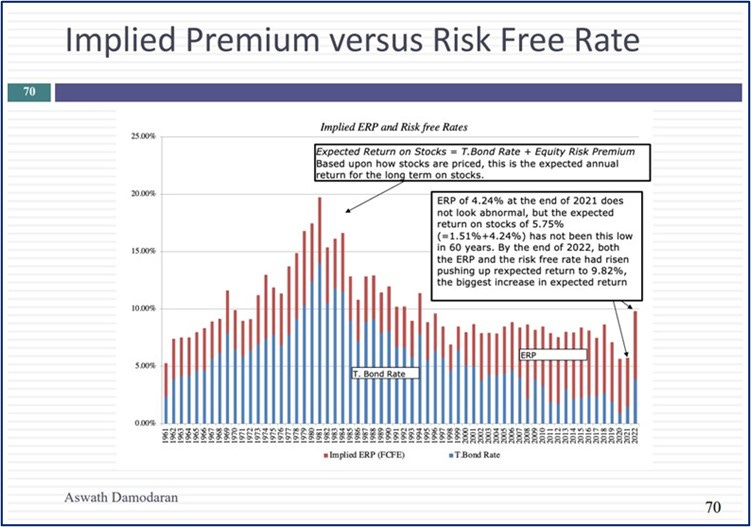

NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran pointed out in his valuation course that the expected return on stocks was the lowest it had been in 60 years at 5.75% at the end of 2021. (This figure is essentially a reverse DCF that solves for the discount rate that would make analyst-forecasted cash flows equal to the current market price. In short, this figure was not low because of an abnormally low equity risk premium, but rather because of an abnormally low risk-free rate.)

Investors were hardly pricing in a 25-100bps Fed Funds rate by the end of 2022. Instead, the Fed would hike seven times in 2022, raising the Fed Funds target rate to 4.25-4.5% by year end. There will always be risks that investors do not or cannot directly account for, except when conditions start to change. However, they must be quick to incorporate these new risks2 into their Risk Circle.

Set the Premium.

As an investor, you must gauge risks and make sure you are adequately compensated for them, similar to an insurance adjustor. You must set the odds of specific risks and decide what matters and what doesn’t.

The quote an insurance adjuster gives a homeowner is like the price an investor is willing to pay for an investment. The perceived risk informs the insurance premium and sets the ceiling on the return. The riskier something is perceived, the more the insurer would stand to make.

Common stock investing is essentially the inverse of insurance. In any given year, an insurer cannot make more than their insurance premium but can lose much more. A common stock investor cannot lose more than their purchase price but can earn much more. However, the importance of pricing risk is the same.

Now, it is an investor’s job to gauge whether a perceived “risk” is worthy of entering their Risk Circle or not. Here is Warren Buffett commenting on his Washington Post investment years later:

I have never been able to figure out why it’s riskier to buy $400 million worth of properties for $40 million than $80 million. And, as a matter of fact, if you buy a group of such securities and you know anything at all about business valuation, there is essentially no risk in buying $400 million for $80 million, particularly if you do it by buying ten $40 million piles of $8 million each.

We could poke fun at market inefficiencies here, but some investors may have had valid concerns at the time. We couldn’t find any investor commentary published in the period, but we can see the Washington Post’s newspaper and broadcasting earnings were essentially flat from 1972 to 1973, and that is on the back of their (and perhaps any newspaper’s) biggest story ever with the Watergate scandal. It wouldn’t have been crazy to think a lot of subscribers were mainly interested in that coverage, and thereafter would be a higher churn risk. In a Charlie Rose interview3 Buffett also notes that the Television licenses were under challenge by a friend of Nixon’s.

And more to the point, the legality of publishing the highly classified Pentagon Papers was ambiguous enough to warrant a Supreme Court ruling, which was so contentious that six Supreme Court Justices wrote their own opinions on the case. And critical to our point, “the court did not prevent the Nixon Justice Department from seeking to prosecute the Times, The Post, and their controlling owners… under the Espionage Act”.4 Would it have been crazy for an investor to wonder whether there was some off chance risk that the Justice Department went after the Washington Post, which even if unsuccessful, could have distracted management and made them more risk averse in future investigative reporting?

Keep in mind, though, that this is one of Buffett’s greatest investments. One that he parades around as an example of market mispricing. And yet, there still was some existential risk to the investment, despite the bargain price.

Regardless of how little you pay, when you are investing there are always these remote adverse events that can impact your investment. According to Todd Combs, he and Buffett talk about:

“How many [companies] are going to earn more in five years (using a 90% confidence interval), and how many will compound at 7% (using a 50% confidence interval)?”

The key words here are “90% confidence interval”, not 100%. Since he is talking about earnings increasing and not contracting, we’d expect an even higher confidence interval for earnings to at least be stable. Either way, the idea is there is always going to be some lingering risk in investing, and dwelling too much on the high impact yet implausible ones will likely lead to you overweighing that probability (i.e. saliency bias) and miss many good opportunities.

Buffett purchased his Washington Post stake at a steep discount to intrinsic value, which may have allowed him to still make a strong return in scenarios where earnings were flat or slightly contracted, but no price reduction can adequately protect an investor against worst-case scenarios. There is a limit to how much price reductions can compensate for risk because no reduction in price can save an investor from the business being worth zero. There are certain existential risks an investor must simply decide whether or not to accept.

There is a whole category of risks when investing that you cannot explicitly be compensated for because no compensation would be high enough, so you are stuck making a judgement on whether you can live with such a risk. The reason for this is simple: while you can always lower the price you are willing to pay, whatever price you pay can still drop 100%. In this interview, Damodaran echoed a similar sentiment:

We capture that risk in two variables. One is a discount rate... The second variable is something people forget, which is for your business to have all of this potential and deliver value, it’s got to survive. Companies sometimes fail. A young growth company, it could have the most incredible potential on the face of the earth, but if it doesn’t make it through the next three years, you’re never going to see that potential. So, to me the two risk variables are, one is the discount rate and second is some measure of failure risk.

It was interesting to hear Damodaran, who comes from an academic background, talk about risk outside of what can be accounted for in the discount rate. But it aligns with the idea of the Risk Circle.

The Risk Circle is the list of risks you demand to be compensated for. All other risks outside The Circle are either 1) existential risks you can live with, 2) ignored because they are too systemic (i.e., ice ages, meteors, or global nuclear wars), or 3) deemed unacceptable, which means you pass on that investment.

There is one other aspect to dealing with existential or highly improbable but high-impact risks: position sizing.

Positioning.

How much would you invest in something that with 90% probability will yield you a 10x return with a 10% chance of going to zero?

Your expected return would be 900%, which is very high in any context. But you can’t put all of your money in it without risking going totally broke, which for most people would be an untenable risk.

The Kelly Criterion is a formula from probability theory designed to specifically answer this question. If you plug these assumptions into to the equation, you get the answer to invest 89% of your money.

However, in reality, you won’t have clean probabilities to punch into a formula, and you would worry about whether there is something you missed. You also may not get a second chance to “bet” if you lose 100% on your investment, so there would be reason to be even more conservative. Ideally, you would be able to find many similar opportunities so if you are unlucky and one investment loses 100%, it is more than made up by the other investments that are profitable. But most investors won’t even be lucky enough to find even one such positively-skewed asymmetric opportunity, let alone multiple.

There is no easy answer to this question, but the purpose of asking it in the first place wasn’t to answer it. Rather, it was to make the point that the only way to truly account for existential investment risk is in position sizing. The only way to avoid losing all of your money on an investment that loses all of your money is to not have all of your money in it.

Having a positively skewed investment opportunity may be a necessary condition to invest in the first place, but it does not inform you how much you should invest in that opportunity: the adverse tail-events do.

An investor should not take a risk they cannot afford to. There is no precise answer here, but Buffett again provides some guidance:

“Never risk what you have and need for what you don’t have and don’t need.”

The risks that you can’t account for with a discount rate, you must account for with your position sizing.5

We will be releasing a new memo every Friday morning. Subscribe below to receive it!

Also check out our podcast, The Synopsis, here: Apple, Spotify)

Caveating that some claim death is a “disease that be cured”… either way, the likelihood you eventually die from something seems inevitable.

We are not suggesting that inflation or higher interest rates should lead you to sell good companies because the prices could drop. Rather 1) there can be adverse financial impact to some companies from higher interest rates, like banks with long duration securities books, or inflation for companies with fixed price contracts and unhedged material costs. If you are a relative investor though, then you needed to be aware that the risk-free rate had a high chance of increasing.

Page 4611 of the Buffett Compilation

This also helps give support to the idea of “max” position sizing and why you may not always want to cost average down on a stock, even if nothing is changed—it is okay to limit the total dollars you want to invest in a single opportunity, even if that opportunity gets more attractive.