What is a Great Business?

A Framework for Building a Deep Understanding of Business.

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo that is available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

On a recent podcast Drew Cohen joined Leandro of Best Anchor Stocks to talk about what makes a great company. Leandro analyzes and follows dozens of high-quality businesses at Best Anchor Stocks. You can find that podcast conversation here.

Additionally, Drew and Leandro both wrote articles on the topic of what makes a great business. You can find Leandro’s article here.

What is a Great Business?

If we were to put the question to you, “what is a great business?”, how would you answer?

Would you hone in on financial characteristics like high cash flow conversion and recurring revenue, or would you point to a competitive advantage that creates a “moat” or a very savvy manager? Do great businesses exist where there is still keyman risk? Or does the very fact that a single person is critical to the business suggest the business isn’t “great”?

If every business in an industry like credit ratings or salvage vehicle auctions has a high ROIC, does that mean the industry is great and not the companies? If an oil company owns a prodigious well, you’d be more prone to say they have a great asset and not necessarily a great company. However, if a company owns incredible IP, like Nintendo, would you say it’s a great company even if monetization of that IP was historically underutilized? Can a great company have no reinvestment opportunities?

What is a great business?

Inverting into a Platitude.

If we were to work backwards, we would be looking for companies that we expect to exist far out into the future and can consistently earn high returns on their invested capital, with some sort of factor that leads someone to reasonably believe they will continue to earn these high returns.

A high and sustainable ROIC that can’t be easily competed away is the sort of cliché answer any investor would give when they say why a company is great. But this is more a byproduct of great businesses and not a causative factor. You couldn’t set about making a great businesses by saying you were going to only focus on high ROIC opportunities—that’s a bit like the efficient market theorists who study Berkshire’s stock picks and think they can replicate Buffett’s record by buying low beta stocks and using leverage (yes, I was actually taught this in a finance class).

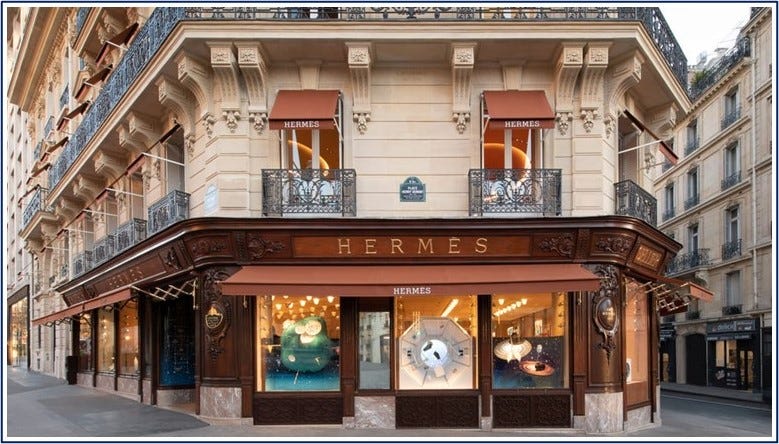

Rather, what we see with most great businesses is they are doing something for someone that somebody else couldn’t do. The best businesses have a service or product that cannot be replaced in a cost-effective manner. Whether that be Floor & Décor selling the widest selection of in-stock flooring at the best money-for-value or Hermes selling $30k Birkin Bags, neither have a direct competitor across all aspects of their value prop.

Competition exists in the flooring market and in the luxury handbag market, but only if the consumer has preferences that are substitutable or forgoable. If they want a Birkin—not just a “luxury handbag”—they do not have alternatives. Similarly, if they want to shop at a flooring store with the most selection of in-stock inventory at the best prices, they do not have alternatives. They may go to other stores that sell flooring, but none will have as many SKUs or as many items in inventory—the consumer would have to decide they don’t care about that if they choose to shop elsewhere.

The Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences.

To elaborate, think of the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences (a similar hierarchy of preferences could exist for a business). From our first memo on the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences:

The Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences is the idea that consumers have an internal “weighting” of desires, and once a desire is filled to a certain degree, addressing their next order desire becomes more important. When a company addresses a sufficient number of a consumer’s desires, they make a sale.

As a company continues to fulfill more and more consumer desires, they start to build “goodwill” or “surplus”. This means that the business is fulfilling more desires than is necessary for the consumer to transact. Surplus isn’t just a theoretical concept though; it is critical to the sustainability of a great business and can clearly be observed by a simple raising of prices.

If Starbucks can increase the price of their lattes to $6.50 without a consumer revolt, then clearly those consumers value the drink, the convenience of Starbucks, and the atmosphere at least that much. However, if volumes dip, as we have recently seen in response to Starbucks price increases, that suggests Starbucks was not fulfilling enough preferences to warrant that price increase.

Of course this is only in aggregate, and certain consumers may value one preference more than another. It is easy to imagine someone who solely goes to Starbucks for the convenience and $1 more isn’t worth them having to make their own coffee or drive further to a different coffee shop. But at some price, they would.

The existence of pricing power is the easiest way to measure whether there is a consumer surplus or goodwill. Creating a product or service to satisfy a customer (or business) is a necessary condition of being a great company. (That doesn’t necessarily mean the customer has to be “happy” about the transaction… more on this later.)

Don’t Mediocre Companies Also Fulfill Preferences?

Now the difference between a mediocre and a great company is how many preferences they fulfill that consumers care about that a competitor couldn’t fulfill. Even the most mediocre businesses are differentiated across some factor, but the problem for them is it is a factor that the consumer is generally indifferent about.

Think of two gas stations at opposite corners. There is nothing different about their product, but by virtue of sitting on different corners they have some minimal level of differentiation. A consumer will have some preference for the gas station that is on the same side of the street as them, but having to make an extra turn is hardly a notable differentiator. This is a very low order preference to the consumer where a 10 cent higher price per gallon could lead to the loss of that consumer’s business.

Mediocre companies serve consumer preferences that are easily forgone or substitutable. Or they wastefully release the consumer surplus they may have had otherwise through mismanagement including poor service and inconsistent experience. When investors say they want a business so great a ham sandwich could run it, what they are alluding to is the fact that the product is so good and creates so much surplus that the management could hypothetically waste a lot of it and the business would still be fine.

Great companies serve consumer preferences that are highly valued by them and hard, or impossible, to substitute. The more preferences a company serves beyond what was necessary to elicit a transaction, the more goodwill or consumer surplus they build.

The Goodwill Pressure Cooker.

The goodwill a business creates is like pressure building up in a pressure cooker where the point is to create as much pressure as possible, while releasing it in the most sustained and deliberate manner.

This analogy can be extended more literally to the oil business. An oil reservoir is pressurized from millions of years of carbonization. When extracting oil from a reservoir, you can easily make a mistake by letting out too much pressure and lose forever the ability to recover some of the oil. An oil operator wants to use the natural pressures that have built up to extract the most oil from the reservoir. There are methods to inject more pressure into the reservoir, but they are costly and often still cannot make up for the loss of natural pressures.

A business is like the oil reservoir or pressure cooker that has pressure that must not be erroneously let out. The more a business does to serve its customers with additional preferences, the more pressure they are building. A scandal, product defects, or bad customer service (the risk of all of which increase with poor management) all expel pressure from the business, but with no gain in return. The proper means of expelling pressure is price.

Price is the mechanism of the pressure cooker’s release, but the transfer can equally be thought of as a transfer of “value”. When we trade with one another we quote it in dollars, but the dollars are merely our best attempt of assigning the value we see in the item. That is why it is common to say a company is charging more than something is “worth”. Serve a decent tasting hamburger for $4 and almost no one would complain, but charge $25 for that same burger and many will be disappointed.

The trick businesses face is a continual and sustained release of the pressure, while simultaneously refilling it at the same time.

Great Companies De- and Re- Pressurize.

Great companies methodically build their surplus and slowly release it overtime. They do not mistakenly let it out through poor business practices.1 (That is much like an oil operator drilling too many pumps on the same reservoir which depressurizes the reservoir at the cost of total recoverability). The only way these great companies ever reduce their surplus is through taking price—and they leave enough surplus so that competitors do not come close.

The easy (if not hackneyed) example of consumer surplus is Costco. They operate with just a 2.5-3% EBIT margin and could very likely raise prices 3% across the board tomorrow with a very limited impact to volumes. With little skepticism, such a price increase would result in a large net increase in profits. However, what they would erode is the consumer surplus. The more they increase prices, the less distance between themselves and competitors. (Additionally, since their model relies on massive scales of economy, unit volume losses could lead to secondary impacts of less preferable pricing. However, that seems unlikely in our 3% price increase scenario).2

In contrast, a company could lose surplus or goodwill without any financial benefit. Southwest canceling 50% of their flights around Christmas time was a great way for them to frustrate a lot of customers. At the point that someone has a cancelled flight on Christmas, their willingness to pay would have likely been hundreds, if not thousands of dollars, to get out of the airport and see their loved ones on Christmas. Those customers’ willingness to pay at that desperate point is a fair equivalent to how much goodwill Southwest lost. There are many customers who simply will never forgive Southwest for those cancelled flights.

Live casino supplier, Evolution, has commission rates that can range to twice as high as the competition. The gaming operators who buy Evolution hate how expensive they are and resent their lack of leverage in the relationship… but it doesn’t matter. As long as Evolution continues to have the best games that players want to play they do not need to leave any goodwill with operators. They can continue to push the line to extract as much value from them as possible. Some may think this is at odds with the Amazon ethos of customer satisfaction, but it is not: how much goodwill does Amazon leave with their merchants?

CoStar’s core product is a real estate data and analytics platform whose customers tend to dislike them because of their aggressive pricing and heavy policing of account usage that occasionally turns litigious. Sure, CoStar could cut their prices 30% and stop monitoring logins so more people like them, but that wouldn’t improve their business. They already have virtually all of the top real estate brokers and 98% retention rates on customers who have been on the service for 5 years. Such a move would impair the exchange of value they could receive over the lifetime of the business. Great businesses do not leave goodwill just because. They do it because it makes it harder for competitors to catch up and increases the longevity of their business.

Think of the LTV calculation. To simplify, it has two variables: 1) lifetime of the customer and 2) profit per period. A great company is trying to maximize for both, and is willing to forgo profit in a given period for a longer lifetime because that will maximize the value it receives over the long-term.

Inside versus Outside Basis.

A great business should not be confused for a great investment. When you are an investor investing in a business, you are doing so on an Outside Basis. When a business makes an investment, it is doing so on an Inside Basis. The differences in return profile can be stark. On an inside basis, a business may be able to open up stores with a <3 year payback, whereas on an outside basis the investor is buying into the business at a 3% earnings yield (which with 7% annual growth implies a payback period of ~18 years).

The need for reinvestment opportunity is the function of the price an investor pays; it is not necessary for a company to be considered great. In fact, the prototypical great business is one that can gush cash without any need to reinvest into the core. If you owned a highly trafficked toll bridge, the need to invest your profits somewhere else does not make that bridge any less of a great business.

Reinvestment is not a necessary condition for a company to be considered great, but it does make an investment much more price dependent. If you pay a high multiple for a business, you need the retained earnings to continue to be reinvested at high rates of return in order for the investment to work. On a long enough time horizon, the premium you pay gets amortized away and the investors’ return converges to the business’s ROIC.

Reinvestment is ultimately a problem of the investors and the price they pay. While of course the business will have to do something with their excess cash, giving it back via buybacks or dividends is a perfectly acceptable answer.

The exception is if management does something foolish with the capital instead because in the long-term that incremental investment would grow large enough to impact the entire ROIC of the business. In 5 years time, the management of a company earning a 20% ROIC would have allocated roughly half of the company’s capital.

Moody’s may enjoy a very high ROIC on their core credit agency business, but they have a very limited ability to reinvest their profits back into the core. In fact, most great businesses are similar, which is in part why they are a great business in the first place: they don’t require much recurring investment.

Many great companies do tend to trade at higher than market average multiples, so the reinvestment question becomes key to the investors’ success, but the problem of an ever greater amount of excess cash certainly cannot be a mark against a great company.

There are No Prescriptions.

While there are commonalities that great businesses share, ultimately though no list is as good as cultivating your own understanding. (They can certainly be helpful to help point an investor on the right path though). The Munger-type of investing differs from Graham in that it is more of a craft and not a rote formula. What that means is it doesn’t require perfunctorily crunching formulas, but the ability to critically think about novel situations.

We started this piece with many questions. But the point was never to give clean answers to them because the understanding that yields the answer is much more valuable than the answer itself.

Walker & Dunlop CEO Willy Walker made the point that his business has no real moats and yet he still 100x’ed the value of the business. GE was thought to be very well managed for a long time, until some of the very management tactics that brought their success were criticized for being too short-term oriented and ultimately were attributed to their unraveling.

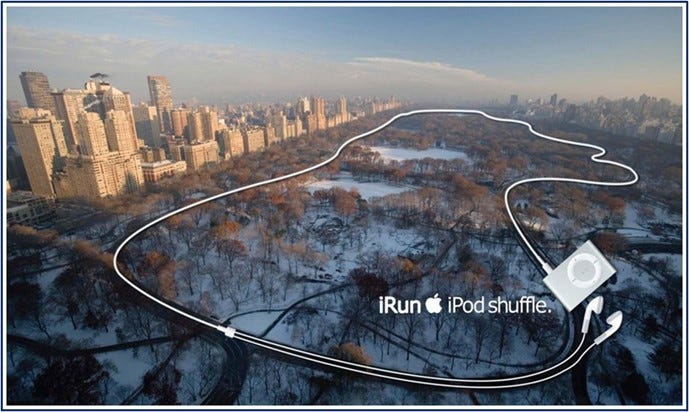

Consumer electronics companies were thought to all be undifferentiated boxes of circuits that primarily compete on specs and price. How would you have understood Apple from this perspective? How long would it have taken for you to realize that there was something special about the company? Would it be after the iMac, iPod, iPhone, iPad, AirPods, or never?

Amazon still gets the criticism that they will never earn an adequate ROIC in their retail segment on their infrastructure investments. And you know what? If Amazon had their way they never would… at least in GAAP accounting terms because every dollar of profit would be reinvested back into the business.

A prescription would have likely had you miss many great companies right up until the point it was nearly consensus they are great. That is not to say their rise was preordained, but rather that giving answers to a question instead of an understanding on how to answer that question would all but destine an investor to miss the next great company that doesn’t look like the last one.

The only way to be able to interpret novel environments is to have a deep understanding of what makes a great business, and much like becoming a great basketball player, it doesn’t just come from watching the tape. It’s in the practice.

Check out our podcast with Leandro at Best Anchor Stocks for more.

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

We also have an interview with Leandro’s Best Anchor Stocks you can find on the feed.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Members Plus also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).

A competitor or new technology could erode a company’s surplus as well. Yellow books and Newspaper had much pricing power before Google and the Internet. Apple’s iPhone quickly made the Blackberry look obsolete and the Model 3 showed EVs didn’t need to compromise on speed and looks (think SmartCar and BMW’s i3).

There is also a tertiary risk that it impacts the culture, which is a more worrisome adverse effect. The multiple impacts from one decision is similar to the idea of decision clusters and the Piton Network we went over in this piece.

Lovely piece, haven't heard it framed with this analogy before (Pressure cooker).

This may be more company specific, but isn't the analogy on Evolution slightly different. They are alienating their customers, whereas Amazon may be alienating their merchants but customers still get the benefit, leaving customers still feeling pretty good about Amazon? However, you could argue that Evolution's customers are not the gaming operators but the users.

Nice article, wonderful insides