WeChat, Meituan, and Grab: What is a SuperApp and Why You Will Fail Building One

Understanding Business Prerogatives as Seperate from The Consumer Value Prop

Welcome to Speedwell Research’s Newsletter. We write about business and investing. Our paid research product can be found at SpeedwellResearch.com. You can learn more about us here.

There is a podcast of this memo available if you prefer listening to it. You can find it on our podcast feed here (Apple, Spotify).

If you are new to Speedwell Memos, welcome! We have pieces on Zara & Shein, Google’s AI risk, Why Wish Failed, Alibaba’s Accounting, What was priced into Home Depot in 1999, as well as many others! Also, if you haven’t already, check out our business philosophy pieces on The Piton Network (Part 1 and Part 2), as well as our Series on The Consumer Hierarchy of Preferences. A directory of our memos can be found here.

An Alternate World.

Despite the ubiquity of coffee shops, there will always only be one that is the closest to you. Even with hundreds of local options, you probably end up at the same coffee shop most days. That is simply because it is the most convenient one for you and that convenience is created by the location’s physical presence.

The rise of digital businesses means that a purely online product would have no in-born traffic advantage nor differentiator stemming from a physical location. Each of these online services would need to earn a spot in the “digital world” whether by launching a marketing campaign to get a customer to download their app or visit their website, or through more creative means like paying billions for a special slot on web browsers or creating hardware to preload your software.

Once a service has a spot in the digital world, they can monetize it directly through selling their own products and services or through advertising.

Facebook and Google of course sell ads, but now even Uber is squeezing a display ad into your ride-hail query. Other internet companies, like South East Asia-based SEA Limited, are far more creative with how they use their digital real estate. SEA Limited employed their wildly popular mobile game, Free Fire, to launch an ecommerce marketplace by seeding the video game with ads and virtual items to compel a user to download their new ecommerce app.

Getting traffic economically and figuring out how to best monetize said traffic becomes the game for internet companies.

What’s so Super about a SuperApp?

Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory points out that in a zero-distribution cost, internet-enabled world competitive dynamics shift as physical barriers that previously contained competition are removed. This results in an increased focus on customer acquisition and retention since distribution is no longer a differentiator. (Think of the classic example of the elimination of the printing press in favor of a computer. This not only meant that anyone could write and distribute their work easily, but also that a consumer is no longer going to subscribe to a newspaper simply because it is one of a few limited options).

A classic means of increasing retention is to get a user to use your product more often. This is commonly done by growing offerings. Convenience stores are commonly paired with gas stations to increase frequency of visits. Markets traditionally may have sold primarily just groceries, but “Supermarkets” have not just a butcher and bakery too, but also may have a flower shop, pharmacy, bank, and coffee shop, in addition to selling a ton of household items. This is all to drive more traffic and build consumer habit, but there is also the ancillary benefit that the more offerings you carry, the greater your ability to monetize.

A supermarket groups together various offerings in hopes that each offering help feeds traffic into other offerings, while simultaneously allowing them to monetize better. The more offerings an individual consumer utilizes, the less likely they are to go elsewhere and the more valuable they become.

A SuperApp is no different.

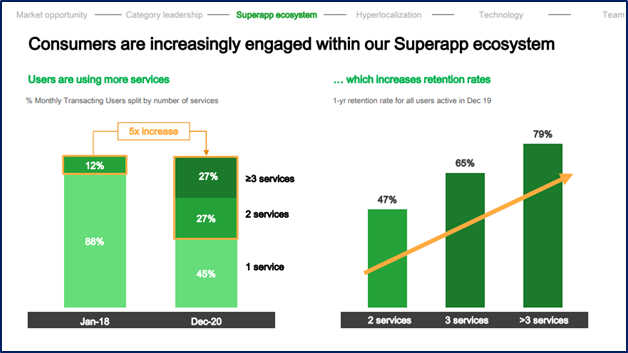

After an internet business solves the hard part of getting users, instead of forking them over to an advertiser’s site or selling them a product, they build up an ecosystem to keep users within their digital confines. They do this by adding more and more services within app, much like the supermarket adding more offerings.

A proper SuperApp effectively acts as a low-cost funnel of future customer acquisition for different offerings by keeping customers captive to a slew of everyday services. The high frequency nature of these “everyday services” keeps consumer churn de minimus. Since the consumer already uses the app regularly, getting consumer adoption for a new service is as simple as promoting it on the home page.

At its best, an app rolls out a new service and can easily get a large portion of their users to sign-up for it. Since it is all in the same app, there is little friction to signing up with preloaded payment and user info. The new service may not only be profitable in and of itself, but increases usage of the app, making it stickier. The increased clicks on the app opens the door for more cross-sell opportunities and perhaps even increases usage of the original service by remaining more top of mind. It is a flywheel at its best.

As great as it this all sounds, it really has only happened once, and the background context that enabled it to happen is equally important.

You Don’t Become a SuperApp by Trying to Become a SuperApp.

In 1998, Pony Ma started Tencent in a small coffee shop to go after the voice and text opportunity in pagers. With the success of AOL’s messaging service, they moved to focus on internet communications, creating “QQ”. By the early 2000s they had over hundred million users, which constituted essentially the entire Chinese internet population. To monetize the messaging service, they turned to QQ coins, virtual avatar customization, and games. When smartphones came, competing mobile-native messaging services started to proliferate, spelling trouble for Tencent’s desktop messaging service.

True to Pony Ma’s competitive spirit, he often pitted multiple teams against each other for the same product. While the QQ team worked on a mobile version, he gave autonomy to Allen Zhang, founder of Foxmail, to create his own mobile messaging service. In 2011 Weixin (known in English as WeChat), was launched.

It flopped.

In the second iteration of the app, they made an important change: the ability to add QQ contacts. At this point QQ had over 700mn users and the same way Instagram bootstrapped off of the Twitter social graph, Weixin was seeded by QQ users.

Once they had this initial user base, they added creative functionality to spur more adoption: “shake” matched you to someone else who was shaking their phone, “Drift Bottle” allowed you to leave a geolocated message for someone else to pick up, and “Nearby” allowed users to see who near them. How critical these features were to their growth is unclear, but the novelty of these features made them popular and within short order they hit escape velocity and were on the road to become the predominant messaging app in China.

Similar to their experience with QQ, once they had that messaging position, they started experimenting with new services to layer into the app, but this time with much more success.

The Backdrop of Weixin’s Rise.

One of the most impressive feats of Weixin is their >3 million mini-programs, which are essentially light apps that are relatively easy for businesses or developers to build. This functionality allows users to do almost anything within the Weixin app, making Weixin closer to a closed “internet” ecosystem than single app. This was only possible though because of a feeble browser-based internet backdrop that enabled it’s rise.

This was for two key reasons: one mobile phones were more prominent than desktop computers from as early as 2014 and even among those who had a desktop, internet connectivity was sparse, usually limited to work or the wealthier parts of the largest cities. In contrast, mobile phones, which connect to the telecommunications networks, could be used in a much broader variety of settings. Time spent online was disproportionately on mobile. For these reasons, it was more popular to build with mobile phones in mind than the desktop.

This context is important when thinking of why mini-programs, which are mobile native and cannot be accessed through the general internet, would be an attractive proposition to small businesses and developers. Why bother building a desktop webpage when it won’t look as good on a phone anyway? Sure, you could build a stand-alone app, but that was far more expensive and harder to do. Plus, as Weixin was quickly becoming an app everyone had on their phone, building for it wasn’t a limitation, but if anything a benefit as it obviated the need to create a log-in account and type personal info. Additionally, similar to the Apple app store, users trusted Weixin enough to blithely download any mini-program. With Weixin pay in 2013 and their own advertising network (which could promote mini-programs), there was even more reason to be inside the Weixin ecosystem.

From the users perspective, mini-programs load similar to how webpages do. However, instead of a clunky interface, they are native to mobile. With a 10mb limit, they are quicker to download than a full app and can disappear after you use them, which was a benefit on slower networks and with the more limited memory capacity of early phones.

The crux of the point is that the mini-program ecosystem served a purpose: it helped get businesses and developers online with less friction, while also making it easier for the user to access.

Bad Intentions.

Attempting to build a SuperApp today though is to put the business’s need above the users’ desires. There are no companies that are happy with their app-based business and decide to become a “SuperApp”. Rather, instead, they are looking to reduce churn, increase app opens, and enter new markets as their pre-existing business is either saturated or floundering.

The problem though is a misunderstanding on why SuperApps were successful in the first place: they served a purpose to the user. Meituan, the China-based company that started out with food delivery, is likely the only other app that comes close to warranting the SuperApp moniker.

Meituan was no doubt trying to solve for a business problem when they added new services, as food delivery was low margin but created traffic from millions of users. Meituan founder Wang Xing decided that in order for the business to be successful they should find a lower frequency, but higher margin service to tie to their high frequency, low margin food delivery operations. Wang Xing created several groups of employees to come up with new business ideas to house in the Meituan app. Hotel bookings were the best answer they came up with.

Importantly though, they focused their efforts on smaller hotels in lower tier cities, which were exactly the sort of hotels that the larger OTAs (online travel agencies like Ctrip, eLong, and LY.com) ignored. After Ctrip gained dominance, they hiked their take-rate up from hotels, and Meituan didn’t, which helped them sign up larger hotel chains. Despite Wang Xing being explicit about the need to create another business to support the food delivery operation into profitability, it wasn’t the business prerogatives that allowed them to win, but rather serving customers with unmet preferences.

They are arguably a SuperApp because the food delivery operation served as a customer acquisition channel for their hotel booking services with greatly reduced customer acquisition cost compared to if it was a stand-alone offering.

In contrast, Grab, which operates in South East Asia and started with ride hail, probably shouldn’t be considered a SuperApp because when they launch additional services they had to heavily promote them to drive adoption.

While they do have data that shows getting a user to use more than one service (ride hail, food delivery, financial services), drives down churn, housing these services together in the same app does not seem to have much of an impact on user acquisition costs. (When they launched deliveries over 100% of the money they took in was rebated back in the form of incentives. Even more recently, they noted that incentives are 14% of GMV in a business that shouldn’t be expected to have a take-rate much more than ~20%).

If a SuperApp needs to pay to acquire consumers to their new service, with no CAC (customer acquisition cost) benefit from housing multiple services together, then there is hardly anything “Super” about their app.

It’s Just Marketing.

Is there any reason a customer needs ride-hail in the same app as food delivery or financial services? And once a user has a separate app for all three services, is one app for multiple services really any sort of a selling point? The desire to build a SuperApp, which bundle services together to reduce churn and increase ARPU, may be good business rationale, but does it serve any incremental consumer preferences?

Meituan’s success in hotel bookings was not because consumers loved the idea of booking hotels in the same app they can order food in. Rather, Meituan’s hotel bookings service was a service that independently served various consumer preferences in a way that pre-existing options did not. Housing it in the existing food delivery app allowed them to acquire users without traditional marketing, but it did not necessarily make the hotel booking experience any better.

Weixin has gone even farther where not only do new services have a greatly reduced customer acquisition cost, they leverage the ecosystem to create entirely unique services—services that served unmet consumer preferences when they were created.

Today though, in a fairly mature app ecosystem, it is hard to believe a company postering their app as the next “SuperApp” as being anything more than marketing given that consumers already have adequate (not necessarily optimal) solutions to whatever ostensible problems a SuperApp would solve.

Focusing on business prerogatives does not usually make a good business. Focusing on unmet consumer preferences usually does.

The Synopsis Podcast.

Follow our Podcast below. We have four episode formats: “company” episodes that breakdown in-depth each business we write a report on, “dialogue” episodes that cover various business and investing topics, “article” episodes where we read our weekly memos, and “interviews”.

Speedwell Research Reports.

Become a Speedwell Research Member to receive all of our in-depth research reports, shorter exploratory reports, updates, and Members Plus also receive Excels.

(Many members have gotten their memberships expensed. If you need us to talk with your compliance department to become an approved vendor, please reach out at info@speedwellresearch.com).

Check out Kaspi